Start-ups are supposed to be solving unmet needs. However, the reality is that almost all needs are being met in one form or another, with some better met than others. For highly penetrated markets dominated by large incumbents, there does not seem to be any opportunity for emerging players.

Shirt-fronting incumbents across the entire market is obviously a suicidal attempt. But there is a way to win, at least to win some of the market, by cherry picking. The incumbents look strong, but when you draw closer, there will be cracks somewhere. The area where the crack is the largest is likely where cherry picking works best. Using Paul Graham's quote:

You notice a crack in the surface of knowledge, pry it open, and there's a whole world inside.

The Underserved Customers

In order to identify the cracks in large incumbents' offerings, understanding their incentive structure is key. From the incentive structure in place, we can easily identify what the incumbents will focus on and what they will let go.

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.

Similar to investment managers, size is a structural disadvantage when it comes to market positioning. Building a specialised offering for a tiny part of the market does not move the needle for large incumbents. Structurally, large incumbents will almost always focus on the mainstream customers in the target market. The implication of pleasing mainstream customers is that they will also distance non-mainstream customers at the same time. Who are the non-mainstream customers? They will differ from the mainstream in at least three dimensions: complexity, niche, or risk.

Mainstream products likely still work for them, but they come with a hefty price or inconvenience. The burden lies on the customers' side, and the resulting tension becomes the foundation for them to be ready to churn to more customised products when opportunities arise.

The Lukewarm vs The Passionate

Start-up venture building in many aspects is similar to growth from a seed to a tree. The seed comes from one passionate group of customers whose unmet needs are large enough to overcome the friction of switching out from existing providers. This initial group of passionate early users is called early adopters in lean startup language.

A rule of thumb is that a new solution needs to be 10X better than the existing solution, famously documented in Peter Thiel's book "Zero to One." Anything less than that just won't cut it, as the experience is just incrementally better, which hardly justifies the hassle of going through challenges and uncertainties in switching.

This is incredibly hard, which is why incumbents still tend to dominate any market at any moment in time. People building an incrementally better product are likely to have a successful SME with a lukewarm customer base, but unlikely to be disruptive, as customer acquisition will always have a hit-and-miss vibe. For a disruptive force, having 10 passionate customers is significantly better than having 10,000 lukewarm customers.

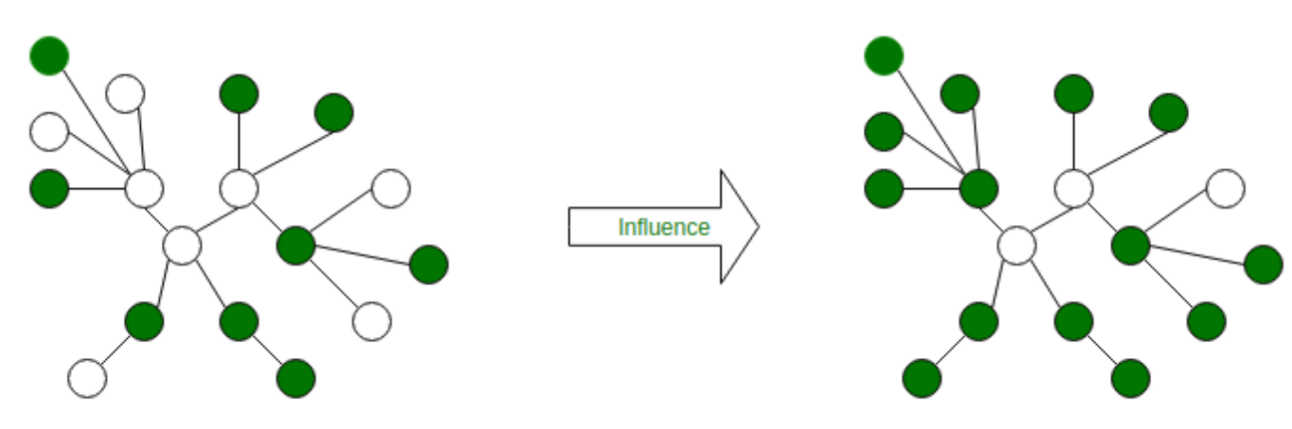

The key to achieving 10x better utility is to start with an embarrassingly small initial customer base and build something so amazing that the customers pull the product out from you. Once this occurs, it is said that Product Market Fit (PMF) for this market has been achieved.

In a great market — a market with lots of real potential customers — the market pulls product out of the startup.

The story does not end here. PMF in the initial markets gives the emerging player the right to exist. Finding PMF in adjacent markets becomes the next best thing to do. This is an iterative and manual process. But once a critical mass is achieved, the mainstream markets become obtainable, and the once humble start-up has a real chance to take over the entire market and even expand it from the incumbents.

Craigslist, despite still having a market cap of $3B in 2024, misses out on much more from the submarkets it failed to sufficiently tap into. Yet a collective of start-ups originating from its submarkets, including Airbnb ($72B), Instacart ($9B), Etsy ($6B), not to mention the smaller players like TaskRabbit, RideAustin, Poshmark, and Thumbtack, extracted significantly more value from Craigslist's submarkets than Craigslist itself.

How Can the Elephant Defend Itself?

There is a force that protects the incumbents - the world doesn't like changes. Disruptive forces are penalized by various natural forces, like how pathogens are killed by our immune systems. For the emerging players, the right to exist needs to be earned. Combining this with the fact that building a 10X product is hard, incumbents are many legs ahead, and the difficulty for incumbents to defend themselves is many magnitudes easier than for the disruptors to win a new market.

Still, the incumbents don't want to sit passively and gamble their fates. The defense approach is strikingly similar to offense covered before: if disruptors cherry-pick to win, then incumbents should segment to defend. It may never be feasible for large incumbents to be as narrowly focused as start-ups, because it can make things look more complicated than they are and risk confusing existing mainstream customers. Further segmenting the products and services to deliver slightly differentiated experiences across various segments is always on the table. Anything is better than a monolithic and unfocused experience determined by the great common divisor across all the customer segments.

It surely does not sound as exciting as the 10x goals that start-ups pursue, but the key goal is to reduce the gap between customers' needs and product utilities to the extent that switching does not look worthwhile anymore. The gap is where disruptive forces breed and thrive. By reducing the gap, the incumbent can 1) trim the initial market size for emerging players and 2) make adjacent market takeover harder. This process is also beneficial for end customers as the entire experience delivered by all market players is improved, just like when Milkrun failed, grocery delivery industry continued to flourish.

Reference

Andreessen, M. (2007) 'The only thing that matters', Pmarca Blog Archive. Available at: https://pmarchive.com/guide_to_startups_part4.html (Accessed: 8 September 2024).

Chen, A. (2021) The cold start problem: How to start and scale network effects. New York: Harper Business.

Ries, E. (2011) The lean startup: How today's entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. New York: Crown Business.

Thiel, P. and Masters, B. (2014) Zero to one: Notes on startups, or how to build the future. New York: Crown Business.