This article provides a brief introduction to a rather mysterious group in the financial markets: the short sellers (Dedicated Short Bias), primarily based on Lasse Pedersen's interview with Jim Chanos.

"Short sellers" is not a very positive term. Choosing to become a short seller means being ready to accept public misunderstanding, unwelcoming attitudes from companies, high tax rates, and the risks of going against the market trend. However, these risks also create opportunities for short sellers.

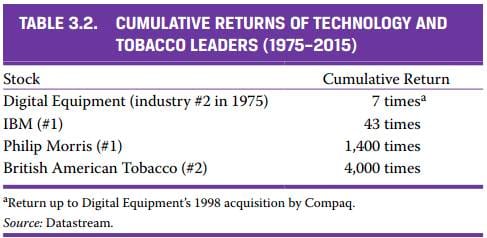

A similar concept is discussed regarding the technology and tobacco industries. Decades ago, it was recognised that the tech industry was the future, while the tobacco industry was destined to decline. The intuitive thought might be to go long on tech stocks and short on tobacco stocks, but such decisions can have the opposite effect. Although tech giants' market values have multiplied significantly, tobacco giants' market values have increased even more, sometimes by thousands of times. This is because the tobacco industry was largely ignored, leading to extremely high expected returns. Short selling, as an under-appreciated craft, could also yield attractive returns by the same token.

The steps for short sellers to make decisions are as follows:

Have a basic idea,

Check if the stock can be shorted—if it can't, it's meaningless,

Conduct fundamental analysis of the company, identifying suspicious areas and gathering all available sell-side reports, while comparing the company to others in the industry,

Discuss your ideas with those bullish on the stock to see how they counter,

Make a decision.

Generally, suspicious signs include declining Return on Capital, or extremely low Return on Capital with extremely high growth—Enron was a case of the latter. If a company's public disclosures are difficult to understand, it might indicate that the company does not want people to comprehend them, signalling potential problems. These are merely indicators, and it often takes a company's actual issues to confirm these suspicions.

Contrary to traditional thinking, short sellers do not visit companies, meet with top management, hire detectives, or consult former employees. The company's top management will not convey any information beyond public knowledge, as it would be illegal. Hiring detectives and consulting former employees are also risky grey areas for short sellers. Their critical information sources are sell-side reports and the target company's competitors.

A perennial question in trading is whether the information discovered is already reflected in the market price. Jim Chanos honestly admits, "I don't know." This is not the greatest risk in short selling. Given that risk premiums are generally positive in the long term, short selling is actually against the trend, and this is not the greatest risk either. The biggest risk in short selling is market short-sightedness and exuberance due to limits to arbitrage. An example is American Online (AOL), which in 1996 was revealed to have never been profitable due to massive write-offs, but the ensuing internet bubble saw its stock price increase more than eightfold, causing significant losses for short sellers.

Professional short sellers do not forget the lesson of diversification. Jim Chanos's rule is to always short 50 companies, regardless of confidence in one's theory, with no single company's position exceeding 5%, while regularly "rebalancing" (see the article on "Rebalancing").

The image of short sellers as evil is deeply ingrained. Many liken short sellers to buying fire insurance on a house about to catch fire, but this analogy severely errs in assuming that short sellers are also the arsonists, which is almost never the case. Companies accusing short sellers often have shady dealings. Over the past 25 years, short sellers have been involved in exposing most corporate frauds. Their presence inhibits the formation of larger bubbles, sometimes benefiting the economy in the long run. George Soros's fame from shorting the British pound in 1992 is often criticised for causing job losses, but Soros still believes that his trade pushed Britain towards a more reasonable development path. The success of short selling lies not in altering the market but in moving it towards greater efficiency.

Short selling remains a highly controversial topic, with many accusations in financial market battles. For instance, fundamental investors might mock quantitative investors as "speculators" whose trades are "ridiculous" without reading financial statements. However, rarely is any group truly "evil"; biases often stem from a lack of understanding. Different market participants' varied perspectives and investment approaches are beneficial for the market.

This short article aims to give everyone a basic understanding of short sellers (Dedicated Short Bias).

Reference:

Lussier, J., Ang, A., Carhart, M., Bodenstab, C., Tetlock, P.E., Hatch, W. and Rapach, D., 2016. Portfolio Structuring and the Value of Forecasting. Research Foundation Briefs, 2(4), pp.1-32.

Pedersen, L.H., 2015. Efficiently inefficient: how smart money invests and market prices are determined. Princeton University Press.

Peterson, R.L., 2016. Trading on Sentiment: The Power of Minds Over Markets. John Wiley & Sons.

Soros, G., 2014. The tragedy of the European Union: disintegration or revival?. PublicAffairs.

Disclaimer: The data and information mentioned are from third-party sources, and accuracy is not guaranteed. This article shares information and views, not professional investment advice. Consult professional advice before making investment decisions.

This article was originally written in Chinese and posted on my WeChat platform in 2016. The Chinese link can be found here