I used to believe that outlier success was mostly due to luck. However, over time, my perspective has evolved and now I can finally put my idea to words.

From a distance, it seems most people are wrapped in a net, much like the sophon in The Three-Body Problem, which encircles Earth and limits its scientific advancement. In contrast, a few live outside the net - riding waves, making history, and achieving boundless success. Once I became aware of this net, I could never unsee it - it only grows clearer with time. If I were to characterise its essence, the word conformity feels most apt. Conformity explains why most people gravitate towards mediocrity in a highly homogeneous way.

What It Takes

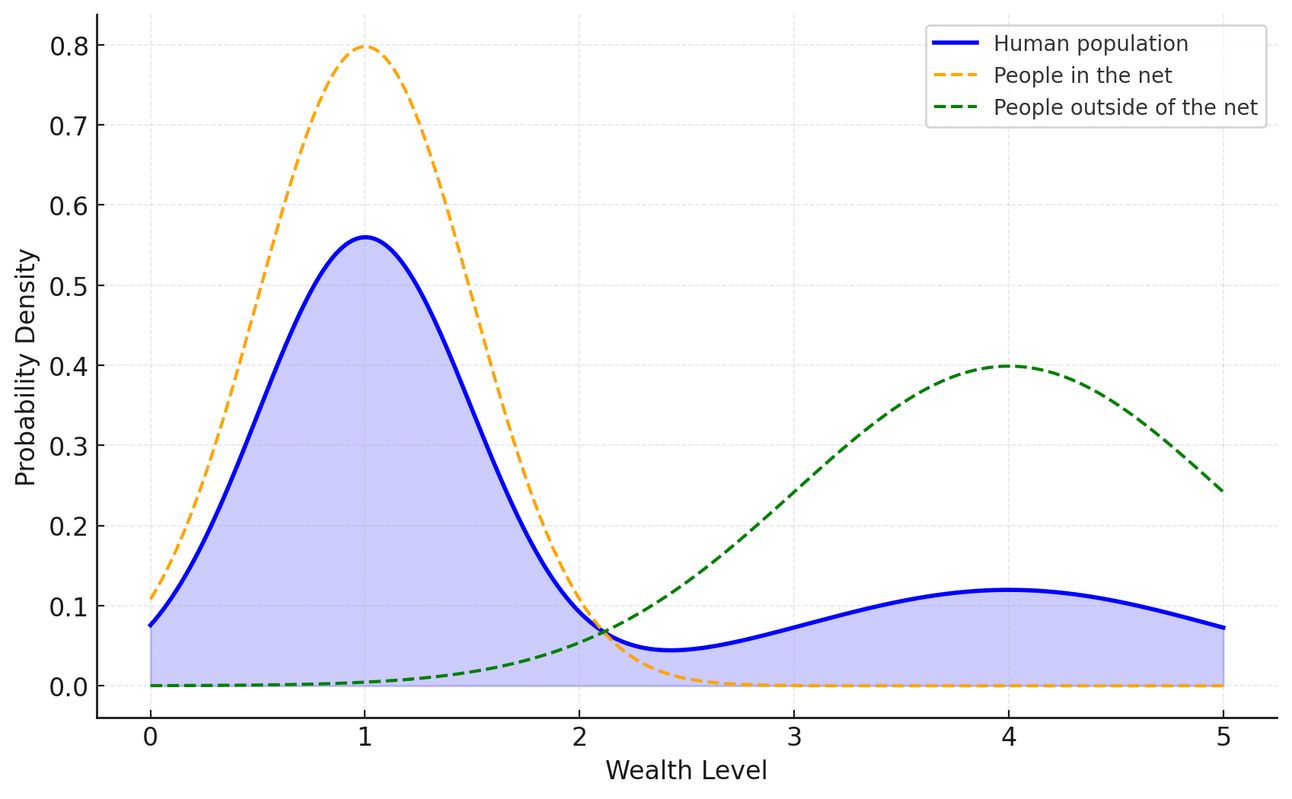

We all know that success in human society is right-skewed, but this skewness may reflect two distinct distributions: one for people living inside the net and one for those outside it. Together, they form the world we know today.

For those who are self-made, regardless of their field, three common elements stand out:

They know something that works

They are able to execute on it

They can keep at it

Having all three will almost certainly lead to success, making these conditions both necessary and sufficient. This perspective is inspiring, as it suggests that success is not as uncertain as it seems. The only challenge is to break free from conformity. However, given that people outside the net form a small minority, breaking conformity is no trivial task. To combat it, we must address the root causes of failure in each of these three elements.

The False Knowledge

The first element is knowing something that works. In the past, when knowledge was scarce and gated, this was a major bottleneck for success. Today, however, secrets are few and far between. For instance, it is widely known that compounding is the eighth wonder of the world, exercise benefits health, and stocks offer some of the highest long-term returns among major asset classes. Regardless of your focus, it's relatively easy to uncover actionable insights that promise long-term returns.

The real issue isn’t the scarcity of good information - it’s the abundance of bad information. Information itself is inert; it doesn’t come to you. But humans do, and much of the world is incentivised to sell something for personal gain. Examples include YouTube dropshipping ads, exclusive clubs, junk food in supermarkets, and communities where the creators are the primary beneficiaries of members' "get-rich" motives.

During my time in the financial advice remediation sector a decade ago, I saw countless cases of well-off individuals losing their life savings. They trusted advisors who, in turn, prioritised low-quality investments offering high kickbacks over their clients’ best interests.

We often say, “Trust the experts,” but this can be false knowledge. At the very least, a “trust but verify” approach is essential. Expert opinion tends to be overrated in two scenarios:

Complex system, such as the economy, investment, and politics

Incentive is at play

Many consider physics to be hard, but it pales in complexity compared to economics and finance, which operate in multiple additional dimensions. As I’ve discussed in my earlier article Uncertainty, experts in these areas often cling to dogmas that fail to deliver alpha. Moreover, when incentives are involved, experts can engage in manipulative behaviours - omitting key information, using vague language, or virtue signalling. This manipulation leads people to consume false knowledge, often to their detriment and the expert’s benefit.

The Strategist and The People Pleaser

The second element is being able to execute. Two archetypes struggle here: the strategist and the people pleaser.

Strategists are intelligent individuals who can articulate the dynamics behind certain opportunities, often with great insight. However, they rarely act on their ideas. When asked why, they offer excuses like needing to refine their strategy or citing external constraints. In truth, they are paralysed by momentum - or the lack thereof.

Strategists often lead comfortable lives due to their intelligence, which makes execution optional rather than necessary. Breaking out of this comfort zone requires persistence, but this is difficult without external pressure. Rationally, strategists may perceive new pathways as riskier and less rewarding, deterring them from taking action. Ultimately, their lack of outlier success stems from their failure to step beyond their comfort zone.

People pleasers, on the other hand, fail to execute because of their attachment to their social circles. Most people live within the net, and they implicitly expect others to remain there too. This is known as social conditioning which is an extremely powerful force. Social conditioning creates downward pressure, particularly on those attempting to climb higher. We’ve all heard stories of people cutting ties with connections that try to drag them down.

As social creatures, humans crave belonging. If your goals diverge from your inner circle’s, you must either conform or face rejection. People pleasers are those who cannot leave their communities to pursue greater things. I suspect this is the most significant factor contributing to the lack of success. The saying “You are the average of the five people around you” couldn’t be more accurate, making it essential to choose your circles wisely.

The Scenesters

The last element is keeping at it. Keeping at it requires deep passion and love, which scenesters lack. No one defines scenester better than Paul Graham.

Scenester means someone who is more focused on seeming cool by doing x than actually doing x.

I don't know about other fields, but in startups the worst thing you can be is a scenester. It's even worse than being stupid. Stupid people can succeed if they try hard enough. But when I hear the founders of a startup described as scenesters, I write them off.

The issue with scensters is that they are status seekers. Their obsession with status-seeking diverts attention from genuine effort. Once the initial spotlight fades, they abandon their pursuits in favour of the next shiny object.

This behaviour is wasteful - not only for scenesters but also for those who support them. Even in the noblest missions, obstacles are rarely glamorous. For scenesters, these challenges are deterrents rather than stepping stones, ultimately leading to failure.

The End

Reflecting on this, I’ve developed a potentially controversial take: the pathway to outlier success is surprisingly homogeneous. The three elements I’ve outlined—knowing what works, being able to execute, and keeping at it - are remarkably consistent across fields. They echo Steve Pavlina’s concepts of truth, love, and power.

The bad news is that failure in any of these elements likely leads to overall failure. The good news? Achieving all three greatly increases the likelihood of success. Mastering them is a process of high precision and high recall.

In the end, failure often stems from conformity - and conformity may be the most significant anti-signal of our time.