People often say that investing is a positive-sum game because the market generally trends upwards over time. Speculation or financial trading, on the other hand, is more of a zero-sum or negative-sum game: for every short-term gain, there’s an equal loss elsewhere. Factoring in transaction costs, trading as a whole often becomes negative-sum. Back in the 1980s, an intriguing academic showdown unfolded—not in university lecture halls, but on Wall Street itself.

The Clash of Quantitative Minds

The 1980s marked the dawn of the quantitative era in financial markets. Investment banks were just beginning to explore how to harness the potential of quantitative talent. Amid this backdrop, a little-known yet fascinating duel emerged.

Fischer Black, after leaving MIT, joined Goldman Sachs’ quantitative strategy department to provide academic insights. During his time there, he identified a curious anomaly in the market. At the time, the Value Line Index was calculated using a geometric average rather than the more commonly understood arithmetic average.

For instance, consider the numbers 2 and 8. Their arithmetic average is (2 + 8) / 2 = 5, whereas their geometric average is √(2 × 8) = 4. It’s mathematically provable that the arithmetic average is always greater than the geometric average.

The Value Line Index futures market prices were based on the assumption that the index was calculated using the arithmetic average. This mispricing meant that the futures were systematically overvalued because, upon expiry, they would converge to the actual index value (which used the geometric average). Notably, there was no spot market for the Value Line Index at the time.

The Challenges of Execution

Traders recognised the anomaly but were unsure how to exploit it effectively. Automated trading systems were nonexistent, and transaction costs were prohibitively high. Buying all the underlying stocks in the Value Line Index could cost more than the potential profits from the strategy.

This was a pivotal moment. Fischer Black envisioned automating trading to free up time for more meaningful tasks. While such ideas were ahead of their time, they laid the foundation for the automated trading systems we take for granted today. Black recruited graduates from top universities to develop this system. Within Goldman Sachs, these recruits were mockingly referred to as “Fischer Black’s PhD students.”

Eventually, they succeeded. Rather than trading all the stocks in the Value Line Index (a costly endeavour), they conducted a correlation analysis to identify a smaller subset of highly correlated stocks. They then shorted the Value Line Index futures. This innovative trading strategy drew suspicion but was groundbreaking for its time.

Victory for Fischer Black

Fischer Black ultimately prevailed. The market recognised its error, and the Value Line Index futures returned to their correct theoretical pricing. However, the strategy was no longer viable for exactly the same reason.

But the story doesn’t end here. As I mentioned earlier, trading is a two-sided game. Let’s talk about Fischer Black’s adversaries: a group of finance professors.

The Professors’ Perspective

The Value Line Index wasn’t just unique because it used a geometric average. It was also an equal-weighted index, unlike traditional cap-weighted indices. This introduced opportunities of its own.

During the 1980s, one well-known market anomaly was the January effect or small-cap effect, where small-cap stocks tended to deliver higher returns in January.

The Value Line Index, being equal-weighted, gave greater weight to smaller companies compared to indices like the S&P 500. This made the Value Line Index an excellent tool to capture the small-cap effect. By simultaneously shorting the S&P 500 to hedge market risk, the professors believed they had a winning strategy.

However, in the end, the professors lost. The January effect couldn’t compensate for the mispricing of the futures, leading to their defeat. Fischer Black emerged victorious.

The Lessons in the Data

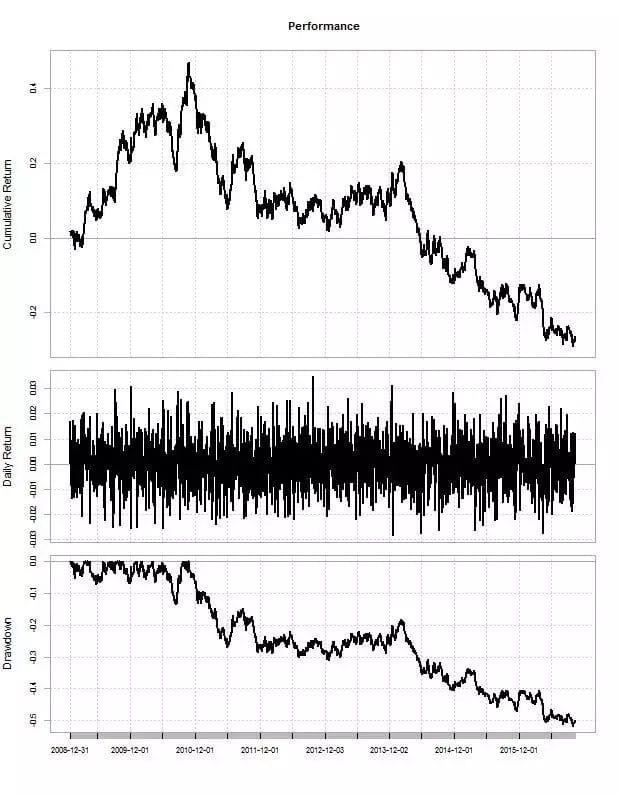

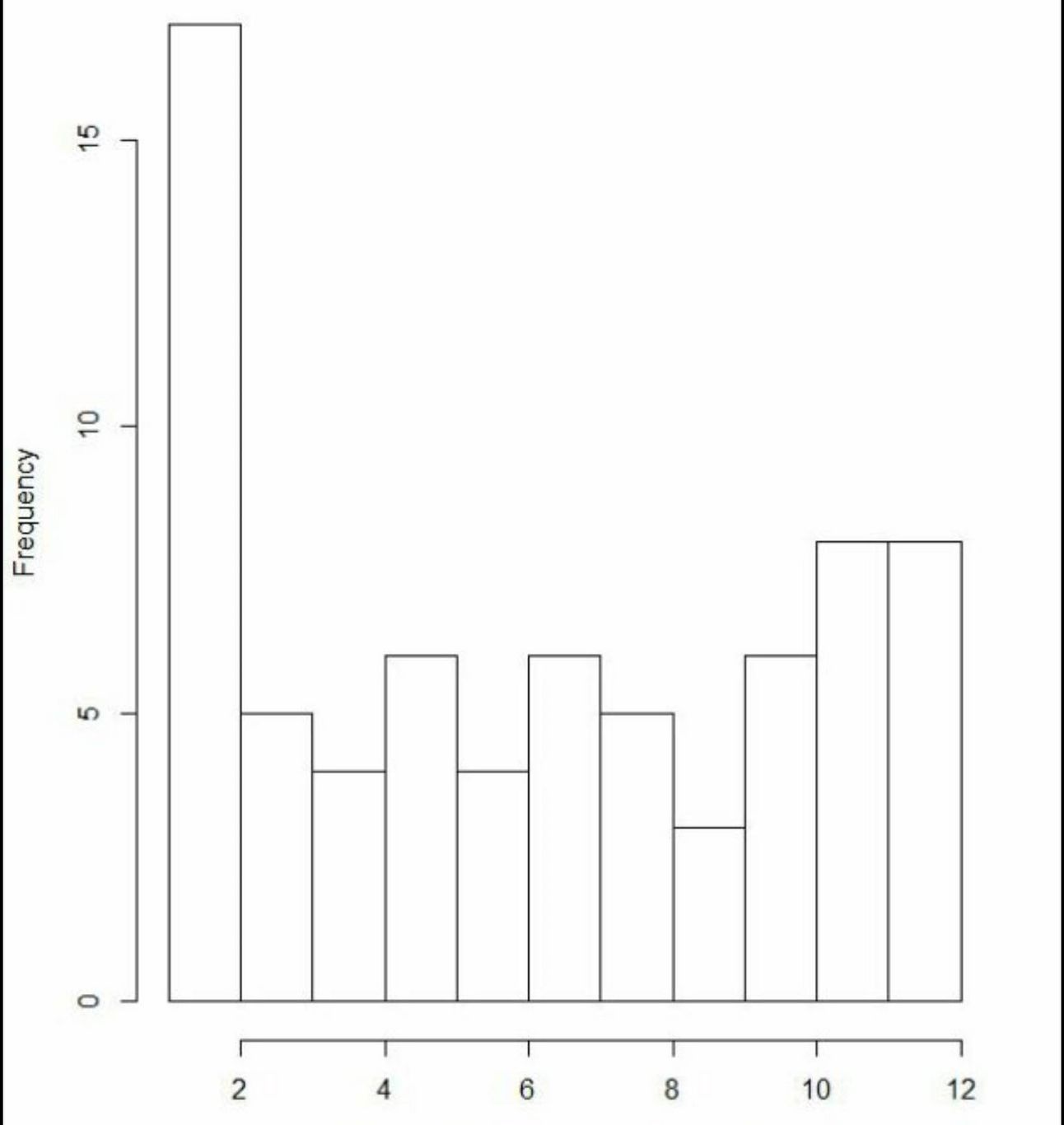

Here’s something to reflect on. Below are two charts. Do you see trend and reversals from the first chart, and January Effects from the second chart?

A stock’s price chart over the past eight years

A chart showing which months small-cap stocks historically delivered the highest returns over a 72-year period.

If your answer is “yes,” congratulations—you possess an extraordinary ability to find patterns in randomness. Here’s the catch: both datasets were generated by me using random generators.

The first dataset simulates daily returns, which are independent of one another. There should be no trends (positive autocorrelation) or reversals (negative autocorrelation). The second dataset assigns equal probabilities (1/12) to each month, meaning the observed January effect is purely coincidental.

Final Thoughts

I’m not attempting to disprove the small-cap January effect entirely. It has since been explained to some extent within finance. My point is that past data often reveals patterns that may be coincidences unless there’s a mechanism to sustain them. For example, value effects may reflect risk premiums (Fama’s efficient market theory) or sentiment reversals (Shiller’s behavioural finance theory). With Risk being inherent or human nature being enduring, value effects’ persistence for centuries can be explained.

Both Fischer Black and the professors were remarkable in their own ways. Their decisions were grounded in sound theoretical reasoning, even for the defeated professors. If the Value Line Index had been arithmetic, the professors would likely have profited. Even without the January effect, equal-weighted indices add diversification benefits and can outperform traditional cap-weighted indices over the long term.

The Value of Process over Results

In our results-driven era, especially in investing, outcomes are often viewed as preordained. I believe it’s more appropriate to evaluate people based on the rigour of their process rather than the outcome.

The act of a man creating is the act of a whole man, that it is this rather than the product that makes it good and worthy.

A trader should be judged on the rationale behind his or her methods and rewarded only if it is sound, irrespective of whether or not he or she profited in the most recent period.

It's crucial to judge the stories traders trade on. Stories can be wrong, but I'm uncomfortable trading without one... Looking only or primarily at their profit and loss statements is a recipe for disaster.

Fischer Black firmly believed in the efficiency of markets, and so do I. While markets are broadly efficient, small systemic pricing errors persist. These anomalies can be identified and exploited, forming the basis of alpha strategies. Discovering and capitalising on such opportunities is what makes alpha strategies truly proprietary—unlike alternative beta strategies.

Sources:

Derman, E., 2004. My Life as a Quant: Reflections on Physics and Finance. John Wiley & Sons.

Mehrling, P. and Brown, A., 2011. Fischer Black and the Revolutionary Idea of Finance. John Wiley & Sons.

Mauboussin, M.J., 2007. More Than You Know: Finding Financial Wisdom in Unconventional Places (Updated and Expanded). Columbia University Press.

Disclaimer: The data and information mentioned are from third-party sources, and accuracy is not guaranteed. This article shares information and views, not professional investment advice. Consult professional advice before making investment decisions.

This article was originally written in Chinese and posted on my WeChat platform in 2016. The Chinese link can be found here