Introduction

Pharmaceutical science has a special place in my heart as a field where I’d envisioned building my career. However, in the end the inherent risks of creating unknown and potentially dangerous chemicals prompted me to pivot towards a safer path within the STEM fields, mathematics.

Fast-forwarding through the years, I found myself engaging in private investments, a sector often perceived as guided by the power law. In some respects, I see parallels to the process of new drug development. My most recent investment endeavor led me to a pre-clinical pharmaceutical start-up. During the process of drafting the associated investment memo, I was struck by the vast scope of the subject matter. Thus, before diving into the specifics of the investment memo itself, I decided to first write down my current approach to investments in the pharmaceutical sector.

The Pharma Business Models

There are three primary business models in the pharmaceutical industry: innovator, generic, and over-the-counter (OTC). These models are distinct from each other in significant ways.

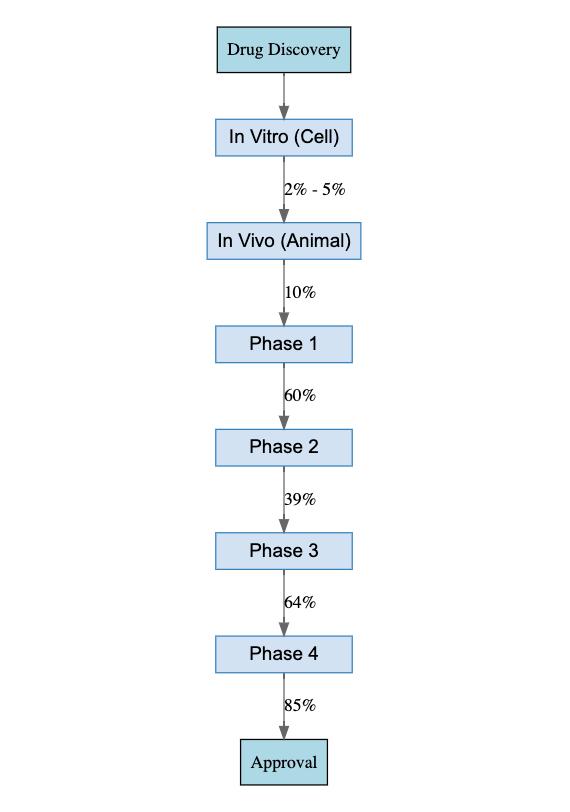

The Innovator model is likely the most familiar to many of us. It involves the development of new chemical or biological entities and requires substantial investments—often amounting to billions—across all stages of clinical trials. The odds of success, from pre-clinical lead compounds to final approval, are less than 1 in 1,000. However, when success does occur, the returns can be enormous. This model is often likened to the start-up culture prevalent in Silicon Valley.

The Generic model comes into play once new drugs reach the end of their 20-year patent life, during which they possess market monopoly. After the patent expires, other pharmaceutical companies can produce a generic copy of the drug. In some cases, the generic company can secure exclusivity for the next six months, allowing them to maintain a higher price point and thereby achieve a substantial return. Contrary to what some might expect, the majority of drugs on the market fall into this category.

Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs are generic medications with a very safe product profile, enabling patients to obtain these drugs without a prescription. The success of OTC drugs hinges on effective branding, customer marketing, product innovation, and more. This category shares many similarities with the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector.

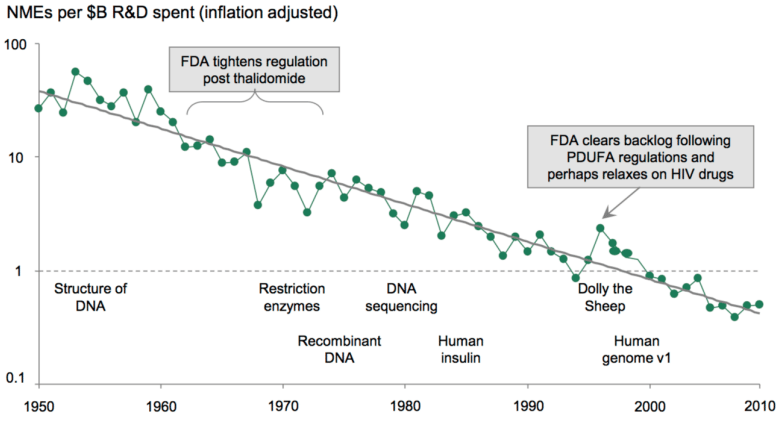

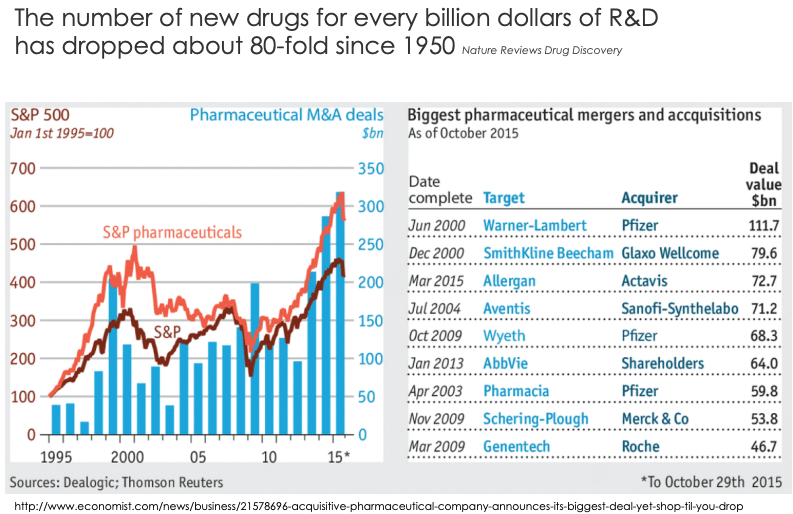

The Generic and OTC models are often dominated by incumbent companies, while start-ups are playing an increasingly prominent role in the Innovator category. This shift is due in part to the struggles within pharma internal R&D to deliver promising new drug candidates, coupled with a sustained decline in productivity. This trend has given rise to intriguing strategic alliances and exit opportunities for early-stage investors. In this post, we will focus primarily on the Innovator category.

The following outlines the key milestones of typical new drug development. Given the odds, succeeding as an innovator is brutally hard.

Preclinical Studies & Clinical Trials

Most drugs we’re familiar with are small molecule drugs, such as aspirin or ibuprofen. However, with the advent of COVID-19, we are also getting familar with biologics like RNA vaccines. Small molecule drugs, thanks to their small size, can often be administered orally and have the ability to penetrate cell membranes to act intracellularly. Biologics, on the other hand, are derived from living organisms and are more complex in structure, which also makes them larger. Due to these characteristics, they often target extracellular sites and are administered through injections. Moreover, their specificity allows them to offer superior efficacy with fewer side effects compared to small molecule drugs, which can often bind to off-targets and result in side effects. By definition, biologics appears to be easier to be first-in-class, best-in-class and structurally unique.

The preclinical stage of drug development is not about randomly creating drugs. It’s much like building a start-up. The first step typically involves identifying a target (a problem). The most rewarding candidates tend to be those that are first-in-class (addressing a ‘new problem’), best-in-class (solving a ‘hard problem’), or structurally unique (thus ‘category-defining’), provided basic safety profiles have been established.

One might argue that certain drugs, such as aspirin, can treat multiple diseases without prior target identification. However, these drugs were generally discovered prior to the establishment of drug regulatory authorities in the 1960s, so historical context plays a role. In today’s regulatory environment, such discoveries are much less likely. As drug development evolves over time, the era of blockbuster drugs is gradually giving way to a rise in specialty drugs.

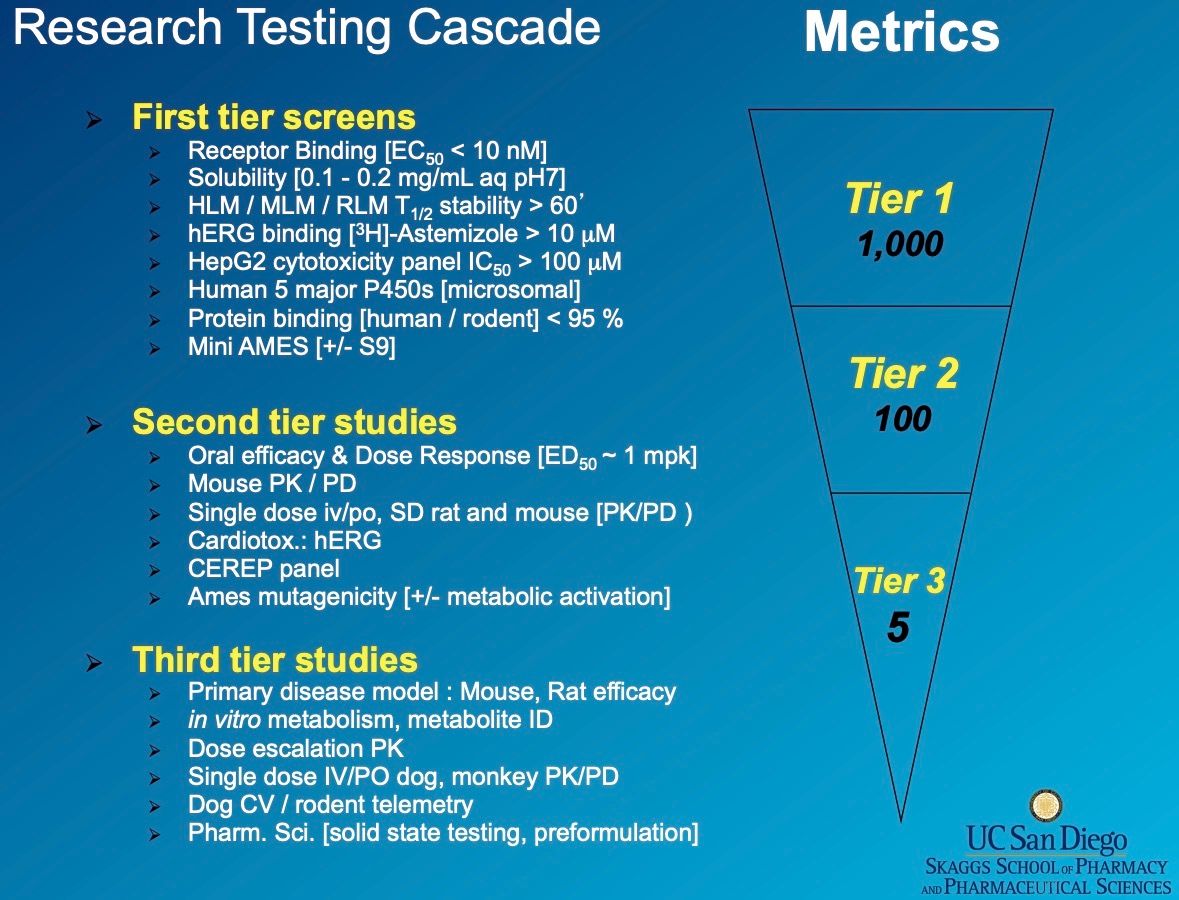

In vitro screening usually relies on research assays, before moving on to in vivo screening using animals such as dogs, rats, or monkeys. Observations from the pharmacokinetic studies in animal trials can be used to inform the initial dosage for Phase I human trials.

Once in vivo screening concludes, drug testing transitions from animals to humans. Typically, this involves four phases of clinical trials, each serving a different purpose.

The primary objective of a Phase I clinical trial is to assess the safety and tolerability of the drug candidate. Interestingly, instead of testing on patients, these trials usually involve healthy subjects (except in the case of terminal diseases) who are expected to exhibit the highest tolerance. This may come as a surprise to many.

Phase II clinical trials evaluate the effectiveness of the drug candidate. In my view, Phase II is the most crucial stage of all. Within Phase II trials, there are two sub-stages: the Proof-of-Concept (POC) stage and the dose-finding stage, which helps determine the dosage for Phase III.

Phase III and Phase IV trials serve a confirmatory role, testing the drug on larger and more diverse population sets.

Strategic Alliance

With the steep decline in R&D productivity, strategic alliances within the pharmaceutical world are increasingly prevalent. These alliances often involve start-ups, research institutes, and large pharmaceutical companies. While I won’t delve into the details of all possible alliance relationships, it’s worth noting that there are benefits for all parties involved. For large pharmaceutical companies, these benefits include risk diversification, expanded product pipelines, shortened product development lifecycle, and cost reduction. Start-ups, on the other hand, gain access to financing, markets, and assets that might otherwise be out of reach. For academic organizations, involvement in these alliances can provide them with fees or research funding.

On average, it takes around 13 years to bring a drug to market, aligning closely with the typical lifespan of a venture capital fund (~10 years). The existence of strategic alliances suggests that exit opportunities for early-stage investors often arise much earlier than the 13-year mark. These exits tend to be binary in nature, with outcomes either being zero or yielding high multiples. This holds true especially when sufficient consideration is given to avoiding ‘me too’ drugs and instead developing ‘first-in-class’ or ‘best-in-class’ drugs before embarking on costly clinical trials.

Conclusion

Many view pharmaceutical investing as exceedingly risky due to the lengthy product development cycle and the low probability of success. However, I take a different stance on this matter. When one considers the expected returns (as opposed to maximum returns) in light of the probability of success, pharmaceutical investing appears significantly more attractive than the return target of a top decile venture portfolio (around 3-4x). By carefully curating a portfolio of pharmaceutical investments, one can potentially achieve high returns with a greater degree of certainty.

Another interesting aspect of pharmaceutical investing, as pointed out by a seasoned angel investor I know, is that ‘you can’t DD the science.’ The human elements that are pervasive in traditional venture investing, from sourcing and selection to post-investment management, don’t necessarily convince me that they contribute substantial alpha to the process. In comparison, pharmaceutical investing seems to provide a purer route to achieving what typical venture investors aspire to, offering both higher return potentials and a high certainty of liquidity.