Passion

It’s all too easy to get lost these days. Environment plays a factor - the rate of changes in the world around us is accelerating, making the half-life of everything we know shorter and shorter. Our own mind plays the other significant factor. I suspect our mind has a type of delayed activation similar to our experiences during puberty, but in a less physical, more mental form. The activation allows us to distance ourselves from the environment we are in and gives us the opportunity to question whether what we have is truly what we want. Yaniv Bernstein, co-founder of Circular and co-host of The Startup Podcast, shared below which many resonated strongly with,

“Most peoples’ goals and aspirations for their life are lazily borrowed from the surrounding culture. Once set, they are bolstered by confirmation bias and cemented by the sunk-cost fallacy. If it takes you only half your life to settle on goals and aspirations that are true to the person you are… you’re ahead of schedule.”

One of the greatest mysteries in the world is, vast majority of people are not working on what they want to work on.

Paul Graham (PG) wrote many great articles, with some changing the venture capital industry forever, some resulting in the creation of the most successful start-ups in the history, and some empowering many people breaking their golden chain and doing something bold, and often great.

One of the masterpieces of PG is How to Do Great Work, which I referenced more than once in my own blog. A key takeaway is to find something that you are excessively curious about to a degree that would bore others, and you don’t feel like it is work even if you pour unusual amount of efforts in it. I would shorten this thing for passion.

Almost all great discoveries or breakthroughs were made by people following their passion, and arguably for the entire history of human race, vast majority of progress comes from a handful of people pursuing their passion.

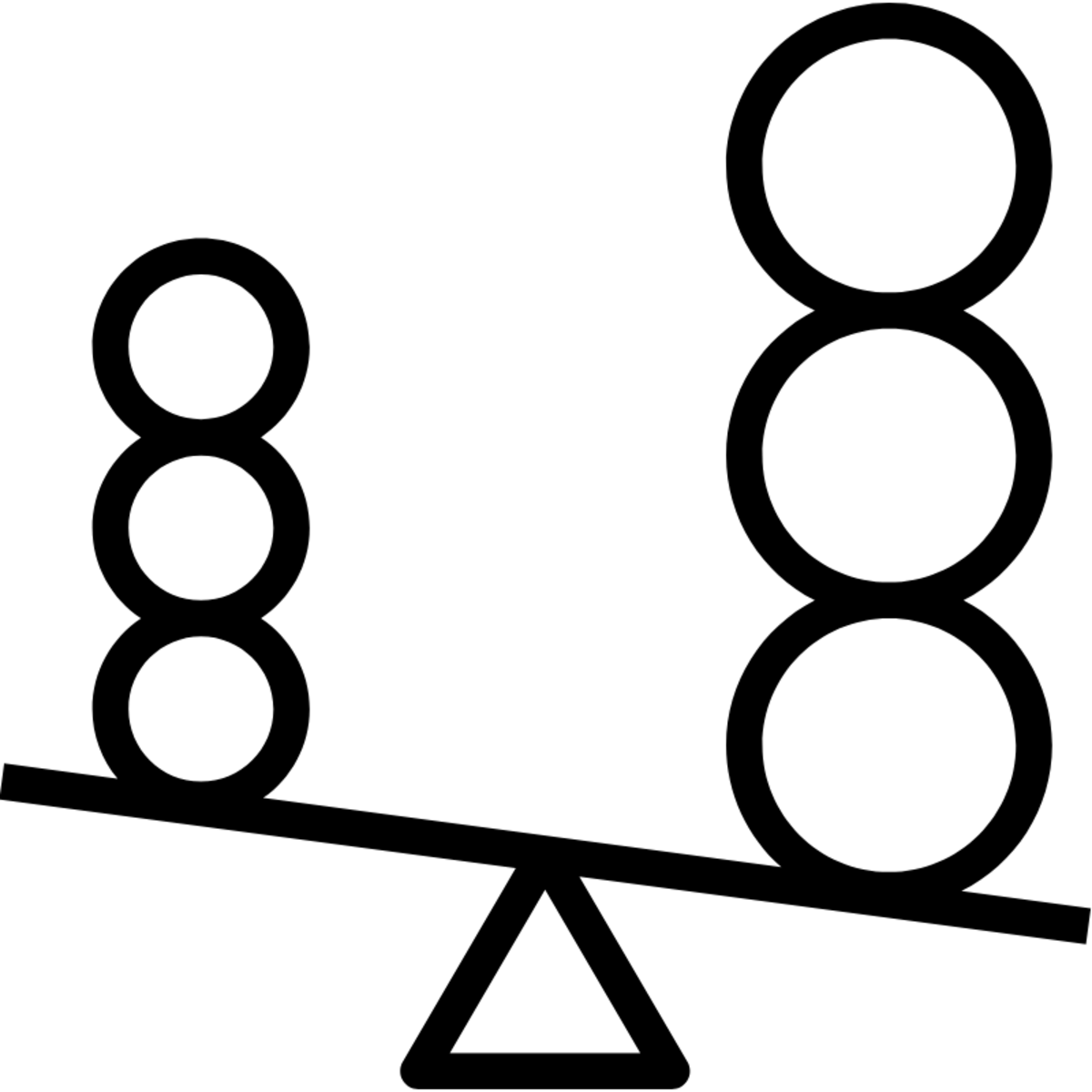

The formula looks simple: passion + hard work. The reality is way harder than it. There is a great deal of pain when one is pursuing the passion.

Pain

Based on my observation, majority of people have their moments of recognising their passion but having to let go of it in the end, due to the pain surrounding the passion.

When one is in school, there is a seemingly fair, but fake metric - the grade. People are expected to perform well in a narrow range of subjects and those that come on top are doing it right and those not on top need to catch up, meaning a change in the way they do things. What if one wants to pursue something not in the curriculum? Most likely it will be killed unless there is a level of customisation in a person’s education journey.

I happened to have visited UCLA today, where Fields Metal winner Terence Tao currently works at. In his early days, without the people advocating for him and shielding him from conventional school education, he may end up becoming another good Asian student attending medical school or law school, as opposed to being a mathematician who elevates the field of modern mathematics. Katalin Karikó, the Hungarian-American biochemist who was rewarded Nobel Prize for inventing mRNA vaccines, had a F next to her name in her upbringing, which stood for fizikai, the Hungarian word for ‘physical’. Essentially it told the teachers that Katalin was from a labourer family and it would be good to get her some extra care. Bill Gates also shared a similar journey early in his life when he got access to computers as a high school student and was able to spend over 10,000 hours on programming before vast majority of universities were equipped with computers.

The fake metric does not stop at school. It comes in various forms in society and traps a lot of really smart people. It could be KPIs, money, social status or virtue, fame etc. Specific to academia, there is also publication list, impact factors, citations, or even dollar per square foot in the University of Pennsylvania where Katalin Karikó worked over three decades in. In the workplace, an employee not meeting KPI would be performance managed. In the society in general, people with the largest amount of money or influence get most respects and attention. In academia, it is up or out based on the publication or dollar metrics. Some could argue that their true passion happens to be aligned with those conventional metrics. I would say it is possible but unlikely, for two reasons. One is that those metrics are output, not input, and they don’t have individuality. Two is that the external validation upon achieving those metrics could easily be mistaken as joy from a person pursuing the true passion. A passion is more likely to be authentic if it doesn’t have come with status or monetary implications.

Not everyone has the environment that empowers them to do something extraordinary and the experience could be especially painful for those who know what their passion is but doesn’t get the opportunity to work on it. There is a great deal of pain, coming from the incompatibility between the passion and the environment that traps most people in. In another word, it is important to recognise that the pain comes from the surroundings of passion, not the passion itself.

The System: Incrementalism vs Breakout

For most things to achieve maturity and stability, a system is required to be in place. It is encouraged to do more of what works and less of what doesn’t work. But systems have a fatal flaw: they rely on historical events to inform future decision making, which by definition, is incrementalism, not breakout. When something incompatible with the system comes in, it will get cleared out similar to how our immune systems kill pathogens.

In fact, the history of science is filled with stories of very smart people laughing at good ideas. This might feel light to say as it implies that smart people eventually get proved wrong and good ideas get implemented in the end. This is not at all the case. What would the world look like without those good ideas? It would look ordinary, or even mediocre, exactly like the world we currently live in. It is the definition of status quo, which is the state of most things today.

On one hand, we need a system in place to be functioning for the vast majority in the world. On the other hand, we need a space for the things that have the potentials to rewrite the playbook to be properly explored by those who are passionate about them. A two universe approach does not seem feasible without great overall costs so the burden of creating such environment nececssarily lies with the individuals, not the system itself. We can do it like how Bill Gates did it, but it required huge amount of wealth. Or we could do it like how Katalin Karikó coped with decades of minimal pay and belittlement.

Two things seem to be required: perseverance and resourcefulness. If a person can’t even feed him/herself, it is without question that this person should aim for survival first, regardless of what the passion is. However, when a basic level of need is achieved, it is a tough choice or rather siren song in front of us - are we comfortable not climbing the social/money/title/fame ladder anymore and instead focusing on something(s) that we love but may not reward us the same way ever?

Conclusion

So, how do we move forward? How do we reconcile the need for order with the imperative for individual expression? Perhaps the answer lies in acknowledging the existence of two universes: the universe of the system, where incremental progress reigns, and the universe of passion, where breakthroughs dance with uncertainty.

The choice is to be made only by ourselves.