Introduction

One of the few widely accepted views about the financial market is that it’s hard, if not impossible, to pick a fund or active manager that consistently outperforms the market index. This belief has been proven repeatedly across different market regimes, various developed regions, and in diverse asset classes. This belief is often distilled into the general principle that the market is unbeatable, leading many to the conclusion that holding index funds is the wisest choice.

While I greatly respect Eugene Fama and recognise that most active managers will likely underperform their index benchmarks over the long term, I hold the view that sophisticated individual investors have a better chance of outperforming the equity market index compared to professional money managers. It’s a challenging endeavour, but it might be more achievable for sophisticated investors than for others.

Market is Not Perfect

The notion that it’s impossible to outperform the market index is fundamentally flawed. Taking the US market as an example, there are at least four major indices that people recognize:

Dow Jones Industrial Average

S&P500

NASDAQ

Russell 2000

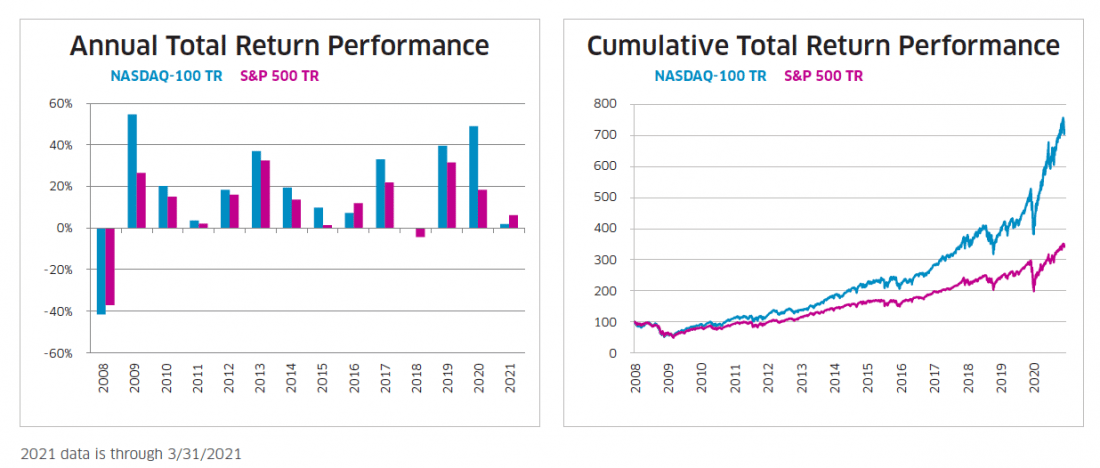

When referencing a market index, which one are we considering? For the argument about the market index to be universally valid, there’s an underlying assumption that all these indices should perform equivalently over the long term. However, this isn’t the case for various reasons. Firstly, there’s the matter of embedded leverage differences. For instance, NASDAQ, with its technology focus, inherently carries higher beta and hence more embedded leverage, suggesting its nominal returns should be higher than those of the S&P500. Additionally, NASDAQ’s risk profile is higher than the S&P500’s due to the substantial representation of high-risk, negative-earning tech companies. Another point of contention is the index construction quality. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, being a concentrated index with just a handful of companies, weights companies based on their stock prices—a factor that might not necessarily reflect a company’s intrinsic value in the public market. Arguably the Dow Jones Industrial Average is a poorly constructed index which can be easily outperformed on a risk-adjusted basis. A parallel can be drawn with Australia’s ASX200, which is notably dominated by major banks and mining firms.

The True Outperformance

A prevalent issue in investment management is the habit of comparing returns on an absolute basis rather than on a risk-adjusted basis. While it might be accurate to state that equities offer higher long-term returns than bonds, it’s misleading to declare that equities outperform bonds long-term without considering their respective risk profiles. Advising individuals to hold a higher equity allocation when young and shift to a lower equity allocation as they age is potentially misguided. The dynamic nature of such portfolio allocation often misses the mark, failing to achieve optimal risk-adjusted returns. Not many realize that a balanced 60/40 portfolio outperforms a 100% equity portfolio on a risk-adjusted basis.

Achieving nominal outperformance seems straightforward — simply adjust the portfolio risks and hope for a fair risk premium, provided it’s executed properly.

The more challenging task is securing higher risk-adjusted returns. Fortunately, we don’t necessarily need alpha at this stage; diversification and tax advantages might suffice for outperformance.

An exclusively single-asset portfolio will always bear inherent concentration risks. Even an equity index, regardless of its number of stocks, can’t diversify away all associated risks. By diversifying into various asset classes that offer fair risk premiums and have low correlations with equity indices, a portfolio can achieve higher risk-adjusted returns than a purely equity-based one. When financial leverage is employed to match the volatility of a 100% equity portfolio, this diversified portfolio not only offers better risk-adjusted returns but also higher absolute returns. Moreover, sophisticated investors can often borrow at rates close to the risk-free rate, adding only 1-2%. Selecting assets that primarily reinvest earnings for capital growth over dividends can result in a borrowing cost even lower than the prevailing cash rate. This tax efficiency can generate alpha without needing to delve deep into capital market inefficiencies.

By this point, we’ve practically outlined a method to confidently outperform the equity market index. But we can further enhance returns by tapping into market anomalies. While this might sound daunting, many alpha-generating strategies are already accessible or even public knowledge. Sophisticated investors can leverage these strategies to surpass institutional investors because they aren’t restricted by substantial asset sizes but have access to complex financial vehicles and tools with reasonably low costs that retail investors don’t have access to.

The Existence of Micro-inefficiencies

Joel Greenblatt and Jeremy Giffon’s concept of special situation investing aptly encapsulates the mindset required to realize excess returns in the financial market. If you’re beating the market, it’s essential to ask: who’s lagging behind and why?

Several reasons come into play:

Risk Premium - You are compensated for taking additional risks, with value investing as an example.

Insurance Premium - Offering certainty to those willing to pay a premium. Commodity trading advisors and volatility selling serve as examples.

Behavioural Anomaly - A delay or inability among market participants to adapt to new market realities, leading to temporary and partial price discoveries. Momentum investing illustrates this.

Regulatory Arbitrage - When regulations favor a particular set of activities or investments, opportunities arise. One example is ex dividend date anomaly specific to Australia.

Mispricing - There is a significant rise of syndication of financial products and automated market making, resulting in persistent mispricing of certain segments. One example is options for biotech stocks and long term options in general.

Limit to Arbitrage - Some securities are overpriced and overcharging systematically benefiting the issuer, but short-selling is not allowed or prohibitively expensive. One example is levered ETFs.

Apart from those listed above, there are also temporary opportunities if you are looking at the right place. However, being able to identify opportunities does not equate to outsized returns directly - it is merely a prerequisite.

Competing in the Right Place

Many view hedge fund strategies as complex, but with the right context, they can be understood. Take one of Long Term Capital Management’s (LTCM) strategies as an example: the yield of bonds isn’t purely determined by their fair price. It’s also influenced by the supply and demand imbalance that arises from certain players’ liquidity matching needs. If the 5-yr bond is overpriced, a synthetic 5-yr bond can be constructed using the 3-yr and 7-yr bonds, allowing us to extract the basis differences through pair trading. Such opportunities remain abundant even today. However, for most of us, this is of little significance as the outsized return is minuscule without leverage—especially once you factor in the cost of short selling. Applying leverage isn’t economical since the cost of leverage exceeds the opportunity size. This style of pair trading isn’t suitable for non-institutional players lacking access to ultra-cheap funding sources.

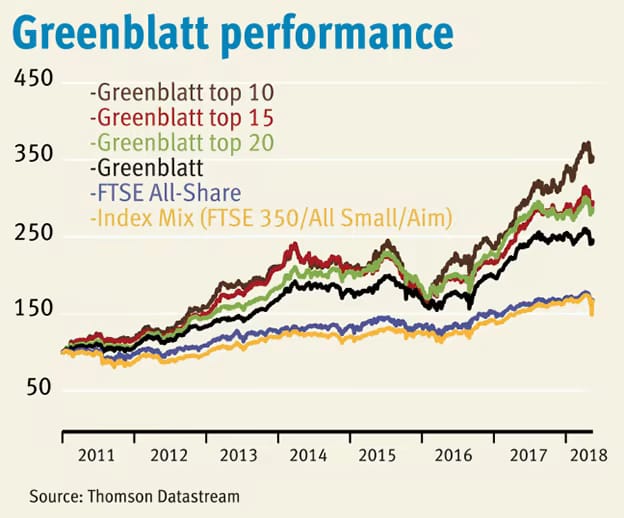

For non-institutional players, alpha is inevitably scale-constrained. This contrasts with the economies of scale observed in business, where scale leads to reduced costs, solidifying incumbents’ positions. In investment management, while scale can reduce costs, it can also dilute alpha. An example is the mediocre performance of multi-factor funds that have anywhere from 500 to several thousand stock holdings. Multi-factor is a potent concept that can outperform the equity market index by double digits when executed correctly. Yet, its advantage diminishes as holdings expand due to the size of the funds—a phenomenon dubbed diworsification. One straightforward remedy is to reduce the number of holdings to those with strongest factor signals, a prime example being magic formula investing.

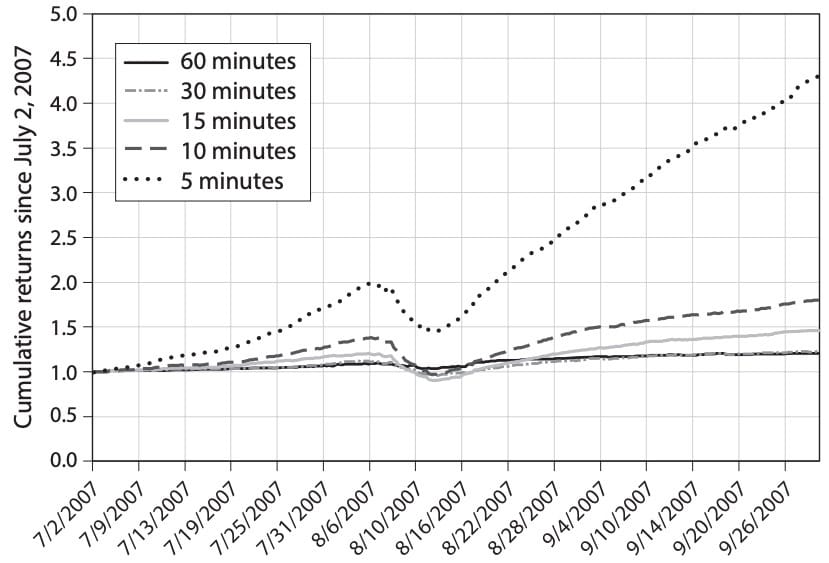

Imposing scale constraints can also be achieved with lower latency or liquidity, as demonstrated by the impressive performance of an intraday momentum strategy showcased below:

Using the venture capital language, a DPI of 3.5 over 8 years can be readily achieved with liquid, marked-to-market public stock holdings. No leverage is needed with the magic formula, which can be likened to an MVP version of multi-factor investment.

I once chanced upon a paper by one of my investment idols from a prominent hedge fund. It outlined a bold investment strategy with a high upside and limited downside based on paper returns. I replicated this strategy in real-time settings, still securing notable gains after expenses. One might wonder, why share a lucrative strategy? The answer: this approach wouldn’t be viable at the scale of their funds (>$100B) or any fund with meaningful institutional size. They saw anomaly identification more as an academic endeavor, leading them to draft a working paper.

What the Ideal Battle Looks Like

If the goal is to outperform the equity index, diversifying across different asset classes, coupled with volatility matching, is often sufficient. However, to achieve large alphas, the strategy must meet several criteria:

a strong source of inefficiency

capacity constraint

cheap leverage

tax advantage

automated execution

A leveraged version of the Greenblatt 10 portfolio satisfies these conditions. Still, more intricate strategies in unconventional areas are available for exploration.

Idea and Execution

In the startup world, an early brutal lesson I learned was the perceived worthlessness of an idea — a sentiment I initially resisted. Over time, I recognised the merit behind this perspective. In startups, the idea is merely the beginning. Founders must constantly adapt, drawing from customer feedback and iteratively build products to achieve product-market fit. This journey demands more manpower, perseverance, and execution than the initial idea itself.

In contrast, investment ideas hold considerable value. Your return potentials will be anchored to the paper size of the identified anomaly. Hence, there’s greater predictability and fewer surprises when crafting an investment strategy. This dynamic closely mirrors the process of inventing new therapeutics, explaining my passion for these two seemingly unrelated fields: investment and therapeutics.

Investments demand execution too. Fortunately, the execution framework needed for high alpha on a small capital base is simpler than for marginal alpha on a large one. Some large fund managers assert they achieve outsized returns and aren’t concerned about sharing their methods. Their confidence lies in competitors’ inability to replicate the intricate execution systems they’ve established.

Conclusion

Lately, my investment attention has been more skewed towards start-ups and private funds due to:

The allure of specific structural advantages implemented by particular players

Fatigue from the ceaseless intellectual quest for alpha in the public market

As I delved deeper into startup investments, I began to notice overlooked disadvantages—some financial, others psychological. Engaging deeply in the startup investing world without getting burnt by the wrong deals necessitates thorough due diligence. However, the ecosystem seems to be moving in the opposite direction, which deeply worries me. Like any good asset allocator, I still believe that diversifying across asset classes is an alpha-generating strategy. Thus, while I’ll continue to invest in startups, I’ll tread with more caution.

Conversely, the public market may seem intricate and even intimidating to some. Yet, it offers a space for discerning investors with unique insights. Surpassing the equity index isn’t an insurmountable task with a well-rounded portfolio. But if the objective is to achieve high alpha, the challenge amplifies due to the need for specialised situations and profound insights. The silver lining? This might be most attainable for adept investors in a non-institutional context.