Since moving into product and growth, I’ve been haunted by a sense of familiarity of mental models common there, like I’m relearning old truths in a new vocabulary. It took me a while to place it, but when I did, the analogy brought instant clarity.

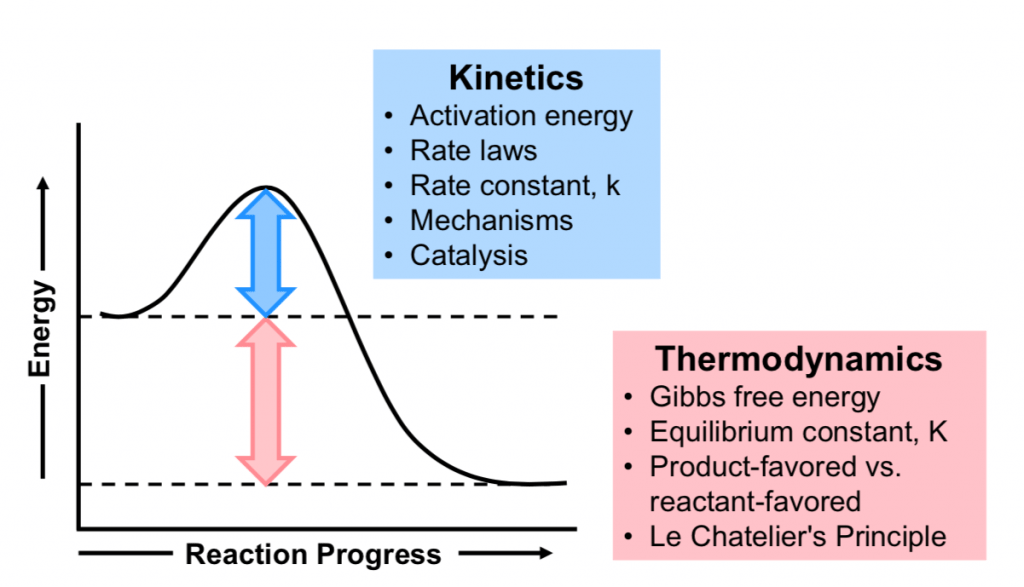

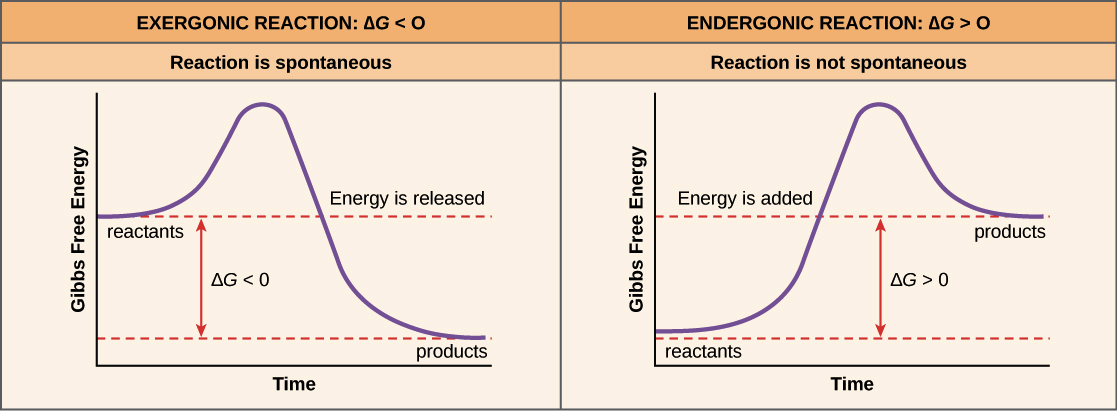

In chemistry, two ideas explain why reactions do or don’t happen: thermodynamics and kinetics. Thermodynamics tells you whether a chemical reaction is feasible in the long term. Kinetics tells you the rate it moves. Even favourable reactions can stall if the activation barrier is too high.

That maps surprisingly well to product and growth. Product is your thermodynamics: is there a real pull: genuine value that makes adoption and retention the natural resting state? Growth is your kinetics: how quickly can you overcome friction, reduce activation energy, and move people from awareness to action? And the reaction we’re trying to drive ultimately is commercial traction.

Activation

Activation is known to be the first area of focus for growth. While the how of activation (setup —> aha moment —> habit loop) is gradually becoming a standard playbook, the why part of activation is still less understood and explained.

Growth typically breaks down into four focus areas: activation, monetization, acquisition, and retention.

Always, always, always start with activation.

The why matters because the playbook is an output, not an input. To write the new playbook, we always have to understand why.

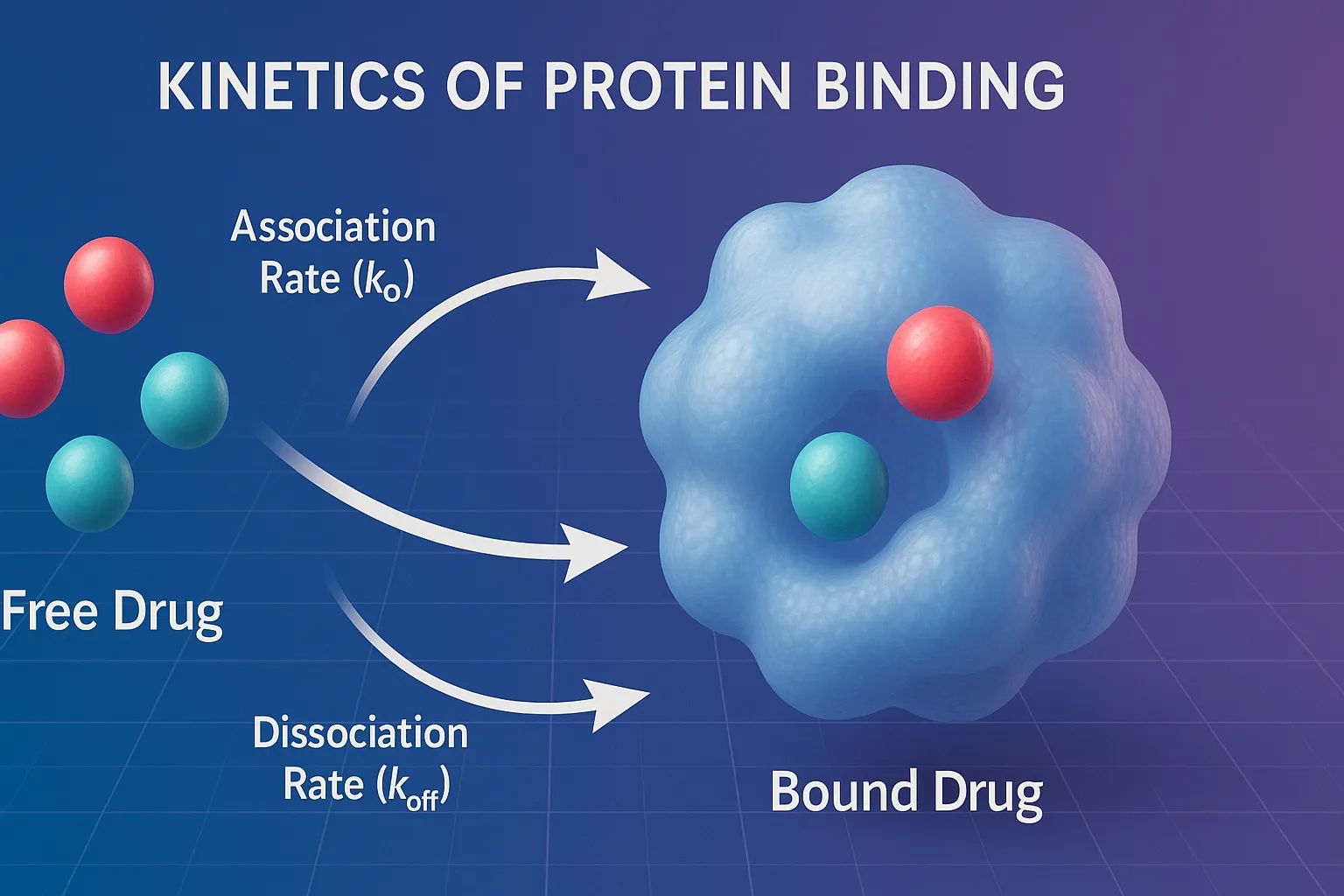

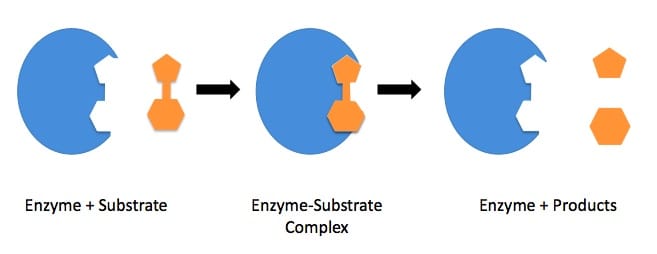

I think of activation as the dynamics of conversion where the chain of events that turns customer interest into real value felt. A helpful analogy in chemistry is that it’s not enough to memorise that a drug works; the more important question is why it works: how it reaches the right place, interacts with the target, engages the right mechanism, and sets off a sequence of changes that ultimately alter the pathological process.

In the same way, activation isn’t just a funnel step. It’s the mechanism that explains why someone moves from exploring → showing interest → committing.

When activation is weak, every acquisition channel looks expensive and ineffective. You can pour more traffic in, run more campaigns, offer bigger discounts, but the system leaks. It’s like an ineffective drug: you can increase the dosage, but you’ll pay for it with rising costs and unwanted side effects.

And the aha moment in activation is the equivalent of a drug finally engaging its target. It’s the first real contact between promise and reality and the moment the user experiences the core value and thinks, “oh, this is actually for me.”

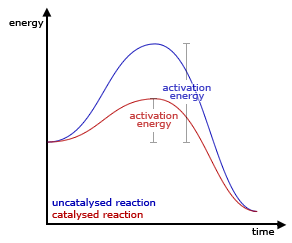

But just because something should work doesn’t mean it will work because there’s still activation energy to overcome. In chemistry, a reaction can be favourable and still fail to take off if it can’t clear that initial barrier.

The same is true for customers. People already have habits, tools, and workarounds. To switch, they need to overcome effort, uncertainty, and risk. That’s the activation energy in growth: the minimum push required for a customer to move from interest to experienced value.

This is why activation should be the earliest focus in growth. If you don’t overcome activation energy, if users can’t reach the first win quickly and confidently, then every acquisition channel becomes a tax. You’ll need “higher dosage”: more spend, more discounts, more follow-ups, more persuasion. And even with a great product underneath, growth won’t be sustainable, because most users never reach the point where the product can speak for itself.

Activation is where growth stops being a push and starts becoming pull. The key lies on lowering the activation energy.

In chemistry, the simplest way to lower activation energy is a catalyst.

Of course, we can’t drop chemical catalysts into a customer funnel. But the principle transfers surprisingly well. A catalyst creates an environment where reactions happen much more easily than they would otherwise. Even more interesting is that sometimes the product of a reaction becomes a catalyst for the next reaction, drastically accelerating the process with time. In the commercial world, that’s how viral growth happens.

There are at least three lessons we can get from the existence of activation energy and the effects of a catalyst.

Lesson 1: Start with the people who need you most.

The customers with a burning problem are far more likely to adopt something new than customers who are comfortable with their situation. They naturally have lower activation energy: less convincing required, less friction tolerated, and a clearer path to an aha moment. This is what Y Combinator calls hair-on-fire customers.

Lesson 2: Make the first value moment delightful, not just functional.

It’s been fifteen years since Eric Ries popularised the idea of the MVP (Minimum Viable Product) in The Lean Startup. But an MVP is not a get-out-of-jail-free card for shipping something mediocre. Especially today, when users have endless options and the cost of building software has dropped dramatically, “it works” is becoming table stakes. The high-leverage moment when customers experience the core value has to be lovable, not merely workable. Delight increases engagement, strengthens conversion, and gives people a reason to talk.

Canva is a great example. It was founded around the time The Lean Startup became the gospel in the tech world, yet one of its growth advantages came from refusing to treat “good enough MVP” as the goal.

Speed is definitely important. Like you can't take 5 years to launch a product, but it also needs to reach a certain level where people get excited about it. You don't just want to launch something that people feel like it just gets the job done but they're not that crazy excited about it. Launching something at Canva that people will spread, they will tell others about, has been the biggest growth driver for us.

Lesson 3: Build growth loops where the outcome creates more outcomes.

This is where the catalyst analogy becomes especially powerful. The best growth systems are loops: each new user, action, or artifact increases the likelihood of the next one. The strength of this effect is often described with a viral factor, the same concept used in epidemiology.

During the early stages of COVID-19, public health messaging focused heavily on keeping this factor below 1, because once it rises above 1, spread accelerates rapidly. Businesses can experience a similar dynamic. When sharing is baked into the experience, growth can compound.

In practice, some companies “manufacture” virality by making sharing feel unavoidable, often through some form of scarcity or social access. Early Facebook, LinkedIn, and Clubhouse all benefited from this at different moments. Others embed sharing directly into the product’s core utility. Dropbox is a classic example, where folder sharing wasn’t a marketing add-on; it was the feature.

Even when the viral factor is below 1, loops still matter. They can play out as referrals, repeat purchases, expansions, re-engagement, or anything where one outcome reliably leads to another. A simple version of this exists in many service businesses: a large proportion of future work often comes from existing customers and their networks. When that loop is strong, every customer acquired is not just one win but a seed for many future wins.

Product Matters

I struggled for a while to understand product’s true role in growth, until I started seeing it through the lens of thermodynamics, the part of chemistry that determines the long term feasibility of a chemical reaction.

In chemistry, even if you can start a reaction, the system still has a preference. When a reaction has positive Gibbs free energy (ΔG > 0) under the current conditions, the products aren’t the “comfortable” state. You might still be able to make some products appear by brute force, by adding energy, pressure, heat, or forcing the pathway, but once that forcing stops, the system drifts back toward what it prefers. The reaction doesn’t hold on its own.

That’s exactly what product is in growth: the long-term preference of the market. Growth can create movement, attention, sign-ups, trials, even short bursts of revenue. But product determines whether the movement becomes a stable outcome, and product does need to earn its right to exist in the world.

A common way to describe product is “turning apples into apple pie.” I like that, but with an important caveat: if the pie tastes bad, people will still prefer the raw apple. You can hand out free slices, run ads, and push people to try it once, but you can’t force them to want it again. Without a product people genuinely prefer, growth tactics become temporary scaffolding: useful for getting started, but incapable of creating something self-sustaining.

This is why I think retention is so often called the “real” growth metric. I agree, but I’d go one step deeper: retention is not the cause, but the symptom. When retention is weak, it usually means the market hasn’t found a strong enough reason to prefer your product over the alternatives and PMF (product–market fit) isn’t there yet.

When product is strong, growth becomes less about persuasion and more about exposure. You don’t need constant “dosage” of discounts, reminders and heavy sales pressure, because the experience itself creates pull. Users return because it works. They recommend because it makes them look smart. Upgrades happen because more value is obvious, not because someone was cornered into it.

So if there’s a hierarchy in the activation → catalyst → product story, this is my conclusion:

Activation is the first moment value is felt.

Catalysts help more people reach that moment faster.

Product is what makes the value worth returning to and the reason growth can compound instead of constantly resetting.

Without a great product, no growth is sustainable. You can push the reaction forward for a while, but you can’t change where it wants to settle.