Investment and the real life used to feel like two different universes to me, as if they don’t share anything in common. That wall between them started melting when I got closer to venture investing, watching how real businesses start, thrive, and vanish, and feeling the full ride of emotions, microeconomics and the very human messiness underneath the every number and choice of words.

I can’t say I enjoy ventures much, but the bright side is that it gave me the realisation that life itself is the biggest capital market for most individuals. Some return profiles in life are unreal, yet individuals rarely take full advantage of them. Opportunities like these in real life, are what I would call real investments.

Unconventional Opportunities

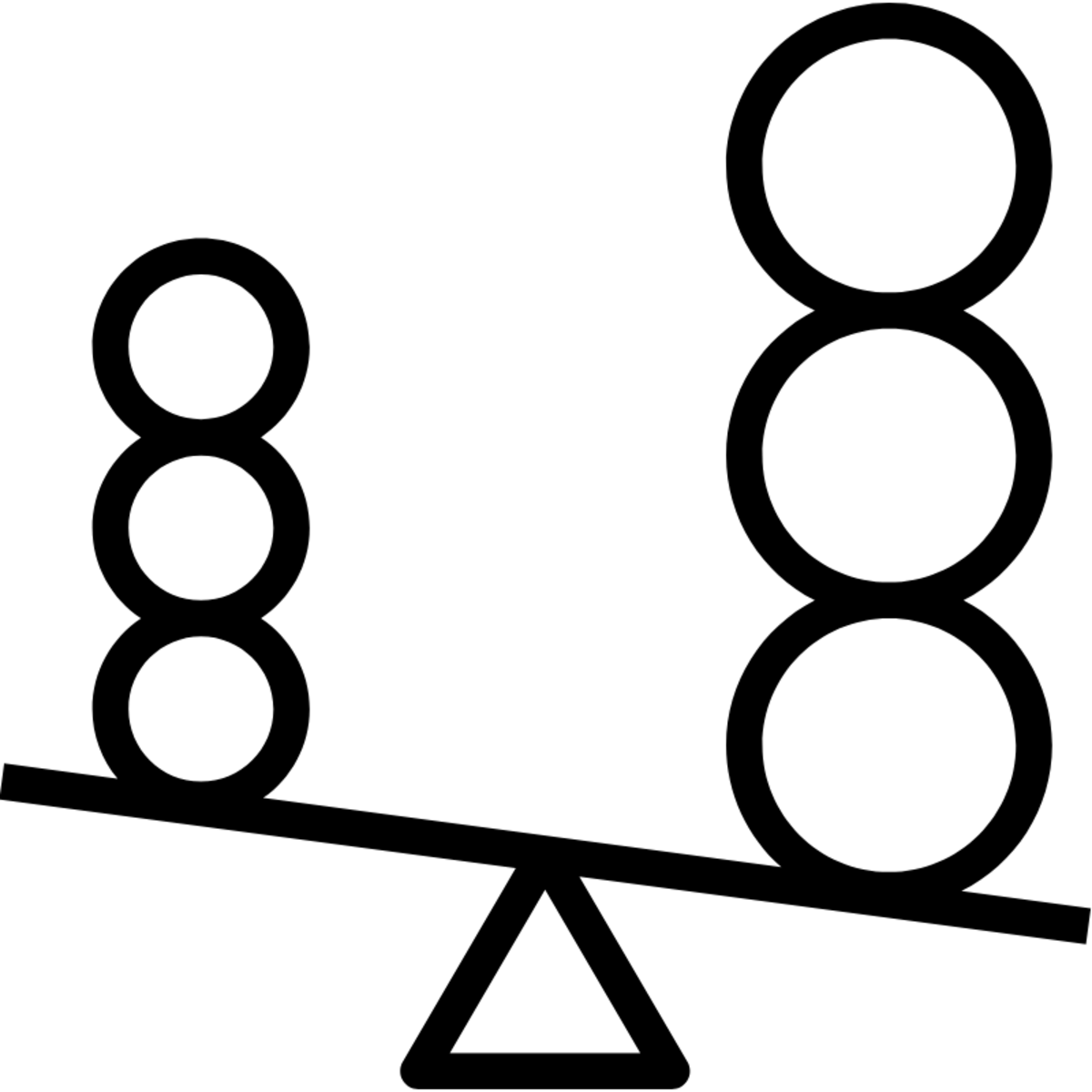

A structured market needs a benchmark. Real investments need the opposite: the ability to defy benchmark. Why? Benchmarks only discipline a market when participants are playing the same game with an agreed measure of “up.” However, real life isn’t a single game. Goals diverge, constraints bind, and many decisions are made for convenience rather than optimisation. Treating life around us as a benchmark does not make economic sense. Real investment is about extracting signal from noise and structuring outcomes in your favour when there is no one else around you doing the same thing at the same time.

A good opportunity by definition will necessarily be unconventional, due to the reason that conventional opportunities are packaged and priced to deliver minimum acceptable returns. The real returns live upstream before the opportunity is turned into a product. Real investment by nature is a craft of active creation than passive endeavour.

Being unconventional is a necessary condition for real investments, but they do need valid reasons to remain unconventional so as not to be productised away. Value capture still follows the chain of sourcing, negotiation, execution and operations. The key factor for real investments to remain unconventional lies on the existence of friction in this chain.

Sourcing: Does the opportunity come to you through proximity but not to others through broadcast channels or due to access constraints (esp institutional players)?

Negotiation: Does the counterparty have special situations that make them emphasise on factors other than maximum value capture?

Execution: Is the execution too small to pay serious attention to but not small enough to be effortless, sitting in the “no one’s lane“ middle ground?

Operations: Are you willing to do what others won’t, not because they can’t, but because it’s rationally unattractive or emotionally aversive (boring, messy, uncertain, repetitive)?

In short, real opportunities are unique in how they surface, in how much outcomes can be reshaped through terms and negotiation, in how they repel most people through work and ambiguity, and in how they ultimately reward only the few who act consistently, not passively.

Understanding Incentives

When I initially learnt about complex systems, systems you can’t reliably predict, yet which describe most of the world, I realised complexity isn’t usually an inherent property of the parts but rather emerges from simple agents following simple rules, interacting over time can produce an effectively infinite range of outcomes.

When it comes to real investment, there also exists a simple yet compelling rule that drives how majority of the world operates: the principle-agent problem.

My personal learning has been that the principal-agent problem drives so much in this world. It’s an incentives problem.

Almost all human behaviour can be explained by incentives. The study of signaling is seeing what people do despite what they say. People are much more honest with their actions than they are with their words. You have to get the incentives right to get people to behave correctly. It’s a very difficult problem because people aren’t coin-operated. The good ones are not just looking for money—they’re also looking for things like status and meaning in what they do.

In real life, we get so carried away by tactics that influence and sales have become a critical skill to master in human society. Window dressing, closing pressure, scarcity, FOMO move us because they effectively hijack attention and compress time. What we should really be looking at is incentives: is the counterparty (agent) structurally motivated to prioritise my (principal) best interest, or merely using me to serve theirs?

This is rarely obvious, because the agent’s rational preference is often the risk-free, minimum-friction path, even when it’s not the maximum collective value path. Their upside may be capped, their downside may be limited, and the costs of thinking harder, negotiating better, or doing extra work may fall entirely on them while the benefits accrue mostly to you. In that setup, “good enough” wins by default, and persuasion fills the gap where alignment should have been. In my opinion, this is one of the biggest problem with venture capital in today’s world, despite the way it brands its business model.

In any scenarios involving incentives, the least we could do is to understand the incentives of the agent. If we don’t, we are navigating in the dark. Where the rule of the game has been set by the agents and the incentives aren’t aligned, walk.

Where the stakes are high and the situation is highly idiosyncratic, the most effective move is often not better persuasions or tighter control, but the creation of incentives because that is usually the biggest lever on outcomes.

Regulations & Government Policies

Being unconventional is said to be a defining feature of real opportunities. But there’s one notable exception: where there are government policies or regulations involved. Policy setting can create a wedge that produces durable opportunities for some. Such opportunities have a gradient of authenticity: they tend to be more real the closer we are to the source of the change, and they tend to be less valuable for the participants the more they are managed by intermediaries.

In Australia, such policies wedges are everywhere, which could be as small as home energy upgrade rebates and home ownership support, or as deep as structural settings that heavily favour particular cohorts, industries, or business models like NDIS, R&D tax incentives, and tax treatments of certain investment behaviours.

Policy wedges are ever harder to get competed away when the rulebook creates bottlenecks through gatekeeping. Based on my recent observations, thanks to the generous Cheaper Home Batteries Program and Small-scale Renewable Energy Scheme, my electrician is now pocketing millions a year while the end consumers land a satisfactory 5-10 years payback on their system installation. This is where the gradient of authenticity of real opportunities truly becomes tangible: the electrician (closer to the bottleneck and the compliance machinery) captures a compounding, scalable wedge, while the household (further downstream) captures a one-off discount that is frequently diluted by sales, markups, and rebate-shaped pricing. In policy markets, the most durable opportunities don’t necessarily belong to the people the policy is designed to help but they belong to the people positioned to process the policy at scale.

One way to capture the policy alpha is to be on the supply side and be the person who productise the rulebook. The world consistently rewards doers over thinkers, and most schemes aren’t implemented by uniquely qualified specialists from day one, but instead by whoever shows up with throughput. This is why entire ecosystems form around policy wedges, for example NDIS providers and plan managers, solar and battery installers, rebate aggregators, where the rulebook creates a bottleneck and the bottleneck prints money. Where gatekeeping exists, competition is slower to arrive, not because the opportunity is hidden, but because the ability to execute at scale is scarce.

The other way is to identify policy wedges we directly qualify for where we can keep most of the wedge instead of handing it to intermediaries. Australia also has many structural settings like this. For example for investors, the tax system can subsidise the cost of carrying an asset when deductions are available, and reward patient holding of assets through the CGT discount. This becomes especially powerful when funding is deployed into low cashflow, high growth assets where investors could achieve a lower cost of funding than institutions, allowing them to pull forward the timeline to financial outcomes by years.

Specific Knowledge

AI is rapidly commoditising general capability at a destructive pace. But that same destruction increases the leverage of specific knowledge, because once the floor rises, the game shifts to the margin. When everyone can produce good enough output on demand, value increasingly concentrates in the small deltas.

This is back to where complex systems matter. In complex systems, simple agents following simple rules create an effectively infinite range of outcomes over time. Markets are the clearest example. The stock market still hasn’t been solved by AI, and it likely never will be. It is not because AI is weak, but because the market is the totality of all agents and feedback loops, and AI is only a subset of those agents. Once AI’s strategies are deployed, they become part of the environment. The environment adapts. Any edge that can be learned can also be competed away.

The practical implication is profound: AI will reduce informational advantage, which will in turn push alpha seekers to pursue positional advantages based on who you are, what you can do, what you have access to, what risks you can hold, what relationships and reputation you’ve earned. Edges will move from analysis to positioning.

That observation generalises beyond markets. In any adaptive system, including competition, culture, business, negotiation, the moment a capability becomes common, it stops being differentiating. By definition, AI capability will become the baseline. Rewards will always accrue beyond the baseline, to the humans and teams who can move upstream by defining better problems, forming better hypotheses, choosing better constraints, and synthesising originality that the system has not yet priced in.

The new “specific knowledge” in the AI era will less likely to be entirely passion driven, but comes with deliberately cultivated uniqueness.

What’s non-obvious in the AI era?

What systems can be put in place that involve other humans?

What new categories will likely to appear?

What risks can’t AI take?

Strategically looking for places where AI is structurally unable to take over becomes a type of specific knowledge by itself.

The End

Real investment is the art of capturing opportunities that don’t announce themselves in our lives. They surface through unconventional situations, incentive divergence, and policy wedges, and now AI is rewriting the baseline, turning what used to be skill into commodity. In the new world, the edge is no longer in knowing more, but in seeing earlier, choosing better, and acting when others won’t. The discipline to manufacture value from real life is where the real return lies.