I went back to my home city in China for a week and was struck by something unexpected. Everything worked perfectly. Food arrived in minutes. Cars showed up almost instantly. Everyday goods felt astonishingly affordable. The efficiency was extreme, almost beautiful. And yet, I felt no emotional warmth toward the businesses around me. When I returned to Australia, the contrast lingered. The difference wasn’t cultural; it was structural. What I experienced was a market optimised to the edge, shaped by commoditisation, platform dominance, and pricing pushed to its limits, and the quiet trade-off between efficiency and trust.

Commoditisation Breeds Specialisation

It took me a while to realise that commoditisation and specialisation are not opposites. Specialisation is not the antidote to commoditisation. It is its natural extension.

As Peter Thiel writes in Zero to One:

A commodity business is a business that produces undifferentiated products.

If you want to create and capture lasting value, look to build a monopoly.

While in business, competition is for losers, it also benefits consumers.

In my home city, a bowl of noodles from the largest breakfast food chain, Cai Lin Ji (蔡林记), costs roughly one dollar. It is difficult to imagine how that price fully covers rent in central locations, labour, renovation, logistics, and various fees and taxes. Yet this is the prevailing market rate.

The same dynamic appears in mobility. While Uber often targets a 10–15 minute wait time in Australia, my experience with Chinese ride-hailing platforms is frequently a two-minute pickup at the equivalent of two to five dollars per ride.

When markets approach commodity conditions at massive scale, two things happen simultaneously:

Service levels improve

Prices collapse

Efficiency becomes compulsory, not optional. In a commoditised market, only the extremely efficient survive. However, even efficiency alone is not enough. If every business is undifferentiated, the market drifts to perfect competition, and there is exactly zero profit for all businesses. This is where specialisation enters, as a structural escape to commoditisation.

In China, there are

Jewellery shops that work with copper as opposed to traditional gold or silver

Beverage shops that name all their drinks from Chinese poems

Even Western food giants like McDonald and KFC aggressively localise, making traditional Chinese soup

Specialisations’ right to exist lies on the realisation that humans are not pure utility maximisers. Humans do crave for culture, taste, aesthetic, and aspirations, especially in higher-value or identity-sensitive purchases. When efficiency becomes table stakes, experience narrative is the only place left where margin can breathe.

Platform As Higher Forces

What struck me most in China was the absence of emotional warmth toward individual brands, even when brand recognition was high. This initially felt counterintuitive as I had assumed that investing in customer loyalty forms the foundation of durable business.

But in a platform-dominated system, that assumption does not automatically hold. Loyalty still matters, but it concentrates at the platform level rather than the merchant level.

Platforms in China function as higher forces. They integrate search, comparison, payment, reviews, refunds, and dispute resolution into a single interface. Switching costs collapse. Friction approaches zero.

And platforms, by design, exhibit winner-takes-most dynamics. As I wrote previously in Evaluating Marketplace Startups, strong network effects tend to push leading platforms toward quasi-monopolistic positions. Over time, they extract a disproportionate share of value from both sides of the marketplace.

The existence of mega-platforms attacks merchants from both the demand and supply side. On the demand side, customers can churn effortlessly between merchants. On the supply side, margins are compressed toward the minimum sustainable level.

Under these conditions, the mathematics of return change. Brands cannot rely on long-term emotional attachment as a stable moat. Instead, they must earn the right to exist transaction by transaction, through product excellence, operational discipline, and algorithmic competitiveness.

It is not that emotional loyalty becomes impossible. It simply becomes economically harder to justify as the primary strategy when visibility, price, speed, and ratings drive immediate conversion. The consequences are visible: family-owned restaurants struggle to compete with scaled chains that optimise supply chains, data feedback loops, and delivery logistics. Institutional operators outperform small businesses not because they are more beloved, but because they are structurally better aligned with platform economics.

The byproduct is subtle but unmistakable: interpersonal warmth is gradually replaced by institutional reliability. The system becomes extraordinarily efficient. And efficiency, under platform gravity, becomes the dominant virtue.

Extractive Pricing Game That Never Ends

If there is one area in business that unsettles me most, it is extractive pricing disguised as optimisation. The pricing system in China is the extreme of it: astonishingly efficient and equally brutal.

For fully commoditised goods, the cost of living can be remarkably low. If you simply want to get by, prices are compressed toward cost. Everyday essentials are affordable. Baseline consumption is efficient.

But beyond that baseline, pricing becomes fragmented, conditional, and strategic.

Take in-store versus online pricing. Unlike Australia, where pricing across channels is generally aligned, physical retail prices in China can be dramatically higher than online equivalents. A mass-market jacket in a shopping mall may be priced north of $1,000, while a similar, sometimes identical item online costs a fraction of that. This is not irrational but rather segmentation.

In-store pricing effectively targets:

Consumers who value the physical shopping experience and are willing to pay for immediacy and ambiance

Consumers excluded from e-commerce ecosystems, such as the elderly

Essentially margin is extracted from convenience and exclusion.

The same logic appears in beverages. Menu prices in-store are often highly inflated. The unspoken norm is that consumers obtain vouchers through mega-platforms such as Meituan, sometimes reducing the effective price by 80% or more. Price discrimination is achieved not through negotiation, but through behavioural filtering. Those willing to search, click, redeem, and optimise pay less. Those who are time-poor or unaware pay more.

Beyond vouchers lie deeper layers: memberships, rotating discounts, referral credits, dynamic pricing adjustments. Even for someone familiar with these systems, the rules can feel deliberately complex.

The result is not inefficiency. It is hyper-optimisation where every segment is calibrated, every willingness-to-pay tier is mapped, and every behavioural friction is monetised.

But the psychological cost is real as the experience becomes exhausting. Consumers grow accustomed to navigating hidden pathways to reach the “real” price. The label price becomes a fiction. The exchange ceases to feel transparent.

In theory, this is efficient market segmentation, but in practice, it erodes trust, at least for me. I asked my family about trust in brands, they were puzzled by this question as if trust was never a factor to consider.

When pricing becomes a game that never ends, value exchange feels less like commerce and more like strategy. Even after a day spent in beautiful shopping malls, eating excellent food, and experiencing world-class service, I returned home subtly drained, not from spending money, but from constantly managing the fear of overpaying. Efficiency might remains, but trust surely does not.

Lessons for Australia

Watching how Chinese businesses operate, my partner and I often felt the stress from miles away. We would imagine ourselves running those restaurants, retail stores, or beverage chains, optimising for rankings, managing vouchers, calibrating margins down to the decimal point. The efficiency was impressive but the pressure was relentless.

Australia is not China. But there are valuable growth lessons here; not practices to copy, but dynamics to understand.

The first lesson is about intermediation.

When platforms insert themselves between merchants and customers, they reshape the economics of the entire market. They push products further toward commoditisation. They collapse switching costs. They expose every offering to instant comparison. In such a world, retention based on friction is a losing strategy. Customers stay only until a better option appears one scroll away. Platforms reward efficiency so the winning product win by optimising for speed, price, and performance.

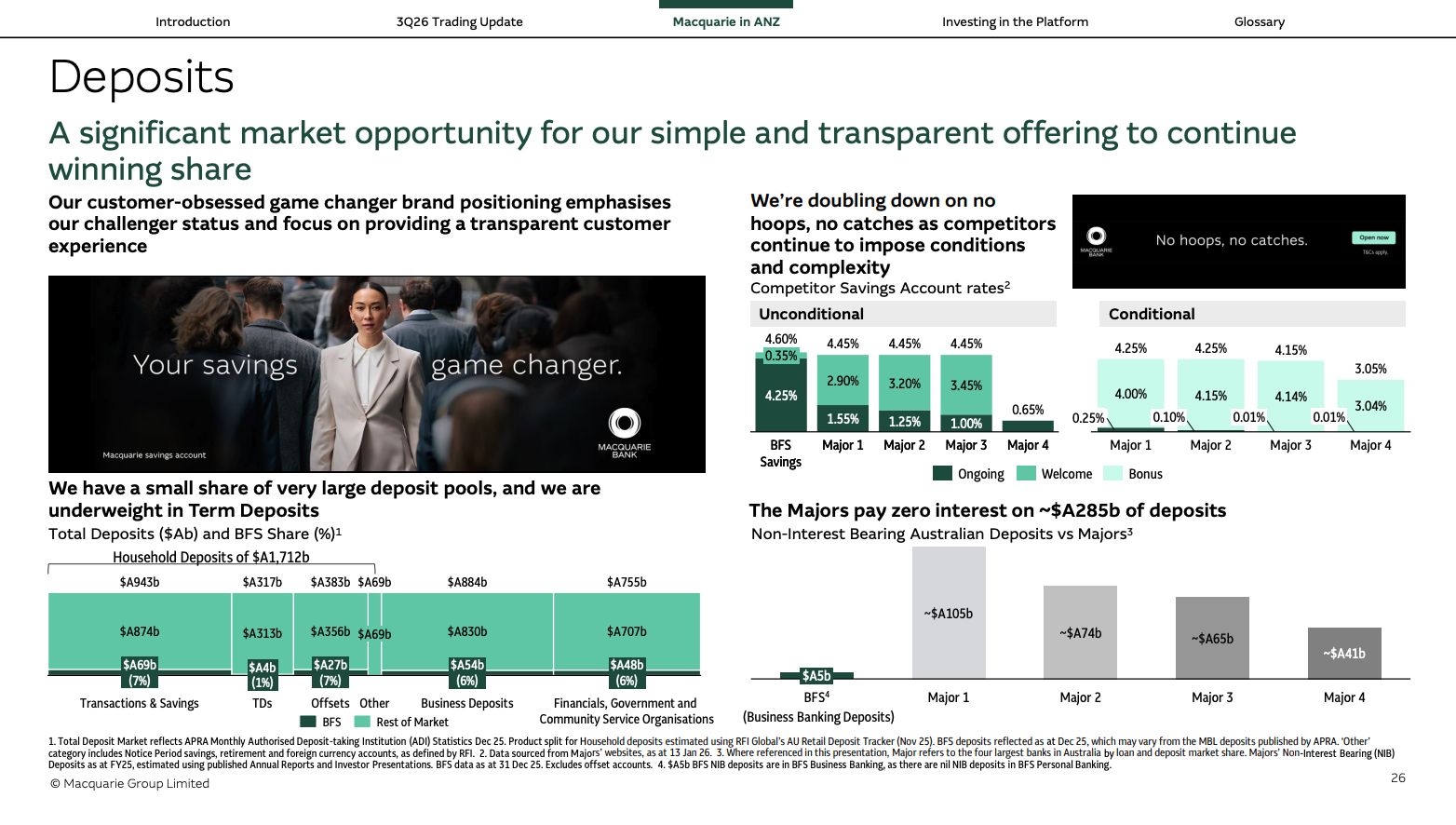

But products that win purely on loyalty operate differently. They often avoid excessive dependence on platforms. They invest in differentiation that cannot be reduced to ranking or voucher logic. They present long-term value clearly and transparently, rather than extracting margin through complexity. Australia still has fertile soil for that kind of strategy, as trust remains a powerful growth lever here. Take Macquarie’s deposit business. Over six years, it doubled its deposit market share from 3.1% to 6.3%. Its approach was not built on pricing tricks or behavioural nudges. It did the opposite: competitive rates, clear terms, no hoops, no hidden catches.

Slide 26, Macquarie Group’s 2026 Operational Briefing

In a world drifting toward optimisation games and extractive pricing, simplicity itself becomes differentiation. China shows us what extreme efficiency looks like under platform gravity. Australian businesses still have the room to choose another path one where efficiency and trust coexist, and where long-term loyalty is earned rather than engineered.