The biggest tech companies in the world are mostly time sinks and tend to follow a product-led growth motion. Traditional companies, on the other hand, are mostly money sinks and follow a sales-led growth motion. As a result, the metrics that matter are distinctly different: for money sinks, the focus should be profitable customer acquisition, not engagement rate, DAUs, or time spent. If you move the wrong metrics, you’ll move nothing that matters.

To dramatically oversimplify the internet, every product on the Internet is just one of two things:

Time sinks. High engagement, sticky, with endless scrolling/tapping. These apps live on the home screen…

Money sinks. Low engagement, you are there to do a job, so you just need it to work…

Sales-led growth and money sinks tend to go hand in hand and can feel low-tech, but it is exactly where AI can play a significant role, even in the current state of agentic AI. While most AI success stories focus on automation and cost cutting, sales-led growth is an increasingly obvious candidate for the next frontier of AI applications.

The Inevitable Growth Agent

If I were to describe what AI feels like to me, I’d say it’s a capable individual contributor: good at producing work from instructions, and happy to work tirelessly with no complaint. What it still lacks is autonomy and the ability to consistently comprehend what truly matters, and to act on expected value rather than on instructions alone. In other words: infinite labour.

Infinite labour is not automatically valuable. In many domains, value is constrained by judgment, trust, and the ability to make high-stakes calls under uncertainty. You can’t brute-force strategy. You can’t brute-force relationships. You can’t brute-force reputation.

But growth in sales-led businesses has a large component that is brute-forceable, because so much of the work is mechanical, fragmented, and attention-bound:

Signals are everywhere (web visits, product usage, call notes, emails, service tickets, renewals, repayments, life events), but rarely in one place.

Decisions are repetitive (“is this customer likely to need X?”, “what should we say next?”, “who should call them, when, and why?”).

Humans are the bottleneck, not because they are incompetent, but because attention is finite.

This is where the “growth agent” becomes inevitable.

When I say growth agent, I don’t mean another customer-facing chatbot. I mean something closer to a sales companion: an always-on layer that observes signals across channels, forms memory at an individual-customer level, and turns messy context into the next best action, while keeping humans in the loop for what humans are uniquely good at: trust, relationships, and judgment.

This also explains why “personalisation” has been a letdown for so long. It has been discussed for years, but in practice it often feels like lipstick on a pig where there’s nothing fundamentally personalised about it. True personalisation means knowing the relevant context for each customer and curating every interaction around their real-time needs and intent. Before the rise of GPT models in 2022, that was closer to utopia than a roadmap. The limiting factor wasn’t the model; it was the sheer labour required to assemble context and craft interactions at scale.

Now the first-order effect of modern AI is simple: it brings infinite labour, and with it, infinite creation as a byproduct. That doesn’t magically solve growth. But it does unlock a new operating model: the ability to do the tedious work required to make sales-led growth feel personalised, consistent, and timely.

And once you accept that, the path forward becomes clearer. A growth agent has three jobs, in increasing order of difficulty:

Capture demand when intent is already there.

Generate demand when intent is weak or silent.

Manufacture trust, or more precisely, uphold trust, because without trust, any optimisation becomes self-defeating.

The rest of this piece is really just those three jobs.

Demand Capture

If a growth agent has an easy mode, it’s demand capture.

In sales-led businesses, demand often shows up in relatively explicit signals: a customer is already trying to do something. Compared to cheap traffic on time-sink apps (social feeds, entertainment, endless scroll), traffic on “job-to-be-done” products is usually higher intent. People aren’t there to kill time but rather to achieve something. In that sense, knowing demand exists is already halfway to acquisition.

The problem is that intent is rarely self-explanatory. In a large enterprise, the same observable behaviour can mean ten different things. Needs vary by product mix, customer maturity, industry, risk posture, relationship depth, and where the customer is in their own lifecycle. The permutation space explodes. This is why “just build a propensity model” has always sounded like a silver bullet and why real success stories are rarer than we’d like. The data is messy, the labels are noisy, and the ground truth is often “what happened,” not “what should have happened.”

The best people at deciphering needs are often great sales, not because they have better dashboards, but because they’re good at connecting dots. They listen for context. They interpret weak signals. They notice anomalies. They remember what was said six months ago and link it to what’s happening today.

For the first time, AI can plausibly scale that kind of sales excellence, not by replacing sales, but by acting as a sales companion.

A demand-capture agent can:

Observe customer behaviours the way humans do (across digital, servicing, and relationship channels).

Assemble context from unstructured sources (notes, emails, documents, call transcripts, tickets).

Form memory at an individual-customer level, so signals compound over time instead of resetting every interaction.

Propose next-best actions with a rationale: what to offer, who should reach out, when, and why.

In its mature form, every customer effectively has an always-on “shadow rep” that watches quietly, connects the dots, and surfaces opportunities the moment the signal appears. Humans stay in the loop, but not merely as a risk-control checkbox. In money-sink businesses, the human is in the loop for what actually moves the outcome: trust, relationships, judgment, and the right tone in a high-stakes interaction.

Demand capture, then, isn’t about blasting more offers. It’s about precision: seeing intent earlier, interpreting it correctly, and turning it into the right conversation, at the right time, with the right human.

Demand Generation

Demand generation is a much harder game than demand capture. If demand capture is “being present when intent shows up,” demand generation is “creating intent when it doesn’t.” Arguably this is where great sales differ from good sales.

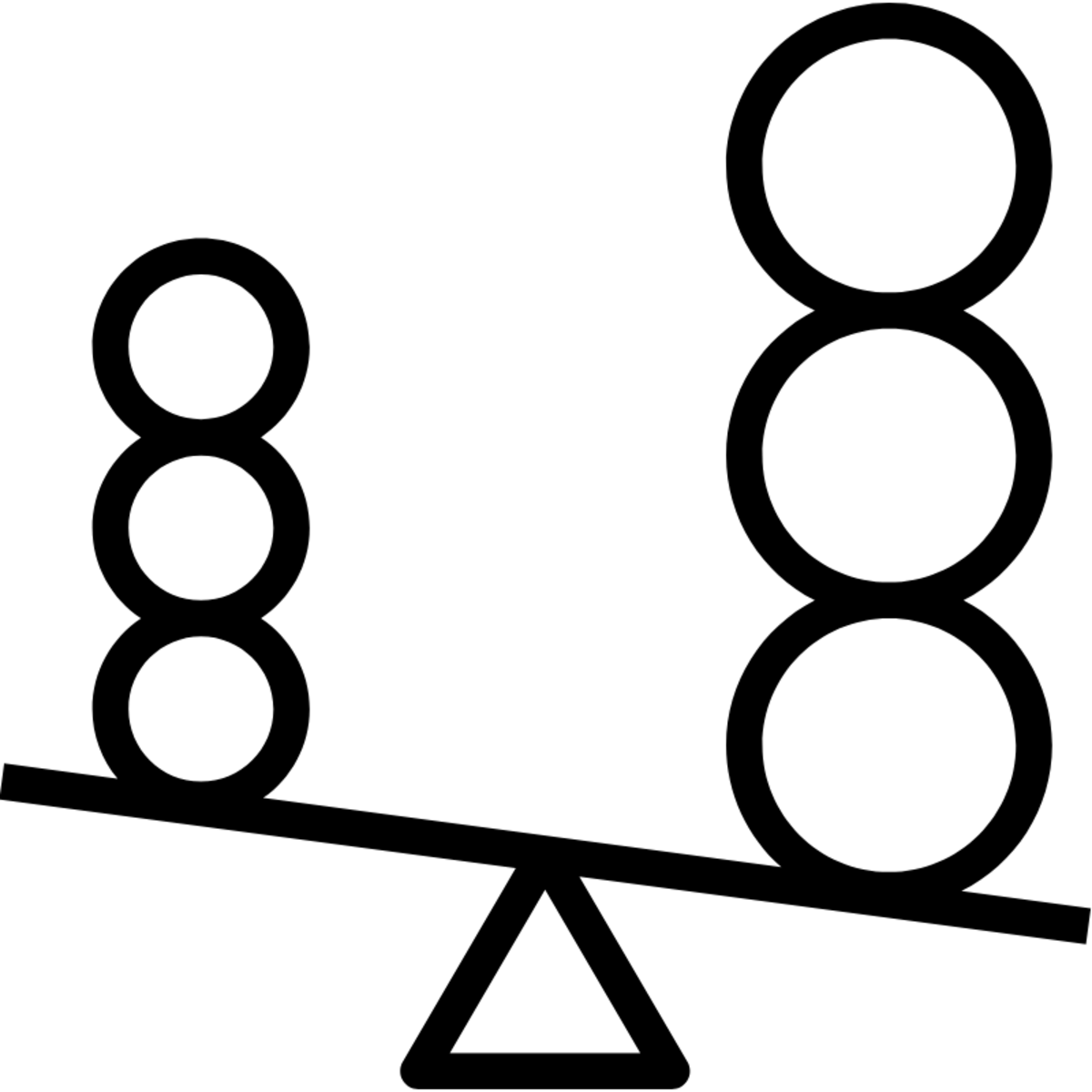

The old saying “attract, not chase” applies beyond finding love. Like it or not, power equilibrium exists in commercial relationships too. The party that chases first is usually the party that wants the deal more, similar to being on the easy side of a two-sided marketplace. This “natural law” is too powerful to ignore, which is exactly why demand generation matters.

Unlike the black-and-white case of demand capture, demand generation works on customers with weak intent, sometimes based on soft signals, sometimes with no obvious signal at all. For them, the activation energy is higher, the sales cycle is longer, and the certainty of their needs is lower. But the prize is much bigger: the population with implicit or latent intent can easily be multiples of the population with explicit intent.

If you are looking for the biggest lever on growth upside, it’s probably in addressing reach…

If you have projects that can target your active users, but not your core ones, then you might have 4-20X more reach!

This is where AI becomes an enabler, not because it can “sell,” but because it can surface truth that is deeply buried under noise, and then help tell a tailored story that creates pull. I see three high-leverage moves.

Uncover silent intent. Customers often have needs that are implied by their circumstances even if they haven’t articulated them, or even realised them. Uncovering those silent intents and advising customers before they ask is like lighting a fire on dry hay. The work is not the advice itself but the detection: connecting scattered signals into a coherent hypothesis of “what might be true.”

Quantify second-order effects. Humans are good at first-order thinking (“this costs money,” “that increases conversion”), and bad at second-order effects (“this temporary hit improves lifetime value,” “this reduces risk and increases wallet share,” “this changes behaviour over 12 months”). One classic play is sacrificing short-term returns to earn long-term compounding where Amazon is the king of this. AI can help by simulating trade-offs, translating narratives into numbers, and making long-horizon benefits legible enough to act on.

Identify hubs and leverage points. Not all customers are equal in influence. Some are “hubs” with outsized ability to broadcast good or bad signals through networks, communities, industries, or procurement ecosystems. The experience these customers receive is highly leveraged, almost like a superspreader effect in COVID. AI can help identify who these hubs are in practice (not just by revenue), and what interventions are disproportionately worth doing for them.

These strategies are non-obvious, below the surface, and hard to execute consistently because they require connecting many dots and telling a convincing story to each individual customer. That’s why demand generation has historically defaulted to spray-and-pray. But a new paradigm is increasingly obvious: precision outreach built on real context, delivered at scale, with humans focusing on the relationship moments that truly matter.

Manufacturing Trust

Once we start generating demand at scale, we run into the real constraint: trust.

A demand engine can be powerful, but power without principles tends to break things. As AI becomes more capable and more autonomous in utility, it inevitably enters grey areas, places where the “right” decision can’t be fully codified ahead of time. A ruthless optimisation mindset will create issues, not because the models are malicious, but because the objective function is incomplete.

Growth is broken. Trust is the fix.

This is the missing puzzle piece: the “soul” of AI. Not in the mystical sense, but in the practical one: an operating principle that constrains optimisation so it compounds rather than backfires.

The uncomfortable part is that this starts with us, not the model. Many organisations already run anti-theses to long-term trust under their own watch. Pricing optimisation with the goal of maximum extraction is one example. The implicit message to customers is that the relationship is transactional; once customers feel that, we become a commodity. Another example is using friction and hurdles as a retention strategy. It may reduce short-term attrition, but it also increases long-term attrition and makes acquisition harder, because customers can smell “lock-in” even before they sign up.

If AI is going to sit inside the growth loop, it has to operate under a trust-first constraint. And ironically, if we get the principles right, AI may be able to uphold them more consistently than humans can, because it doesn’t get tired, it doesn’t get greedy in the moment, and it doesn’t quietly shift standards under pressure.

So “manufacturing trust” is the wrong phrase. Trust can’t be manufactured. But it can be earned through consistent behaviour and it can definitely be destroyed by short-term optimisation. In sales-led businesses, where relationships and reputation are part of the product, trust isn’t a soft value. It’s a hard growth input.

I am convinced that the next wave of AI value won’t come from cost takeout. It’ll come from growth.